Nota Bene: In preparing this answer, I in my haste used $\phi$ for the potential instead of the OP's $V(x, y)$; I have let it so stand to avoid the editing a change would entail. Ah well, as Treebeard the Ent might say, "hrooooom, hrooooom, let us not be hasty!" Sorry for any confusion, and remember, here

$\phi = V. \tag{0}$

This being said:

According to our OP hello, we can take as given the evident fact that

$\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y} = \dfrac{\partial g}{\partial x}. \tag{1}$

Denoting the vector field $(f, g)^T$ by $X$:

$X = \begin{pmatrix} f(x, y) \\ g(x, y) \end{pmatrix}, \tag{2}$

we see that (1) implies that

$\nabla \times X = 0, \tag{3}$

which in turn implies the existence of a function $\phi(x, y)$ such that

$X = \nabla \phi. \tag{4}$

(3) also implies, via Stoke's theorem, that around any (sufficiently smooth) closed path $\Gamma$, we have

$\int_\Gamma X \cdot ds = \int_\Omega (\nabla \times X) \cdot dA = 0, \tag{5}$

where $\Omega$ is the region bounded by $\Gamma$ and $dA$ is the corresponding area element. (5) in turn shows that the function $\phi(x, y)$ may be defined, up to an arbitrary constant, by

$\phi(x, y) = \int_\gamma X \cdot ds \tag{6}$

for any path $\gamma(s)$ joining some fixed point $(x_0, y_0)$ and $(x, y)$, since (5) in fact implies such integrals are independent of the particular path chosen. We are thus free to evaluate $\phi$ by using a path of exceptional convenience. Since $X$ is defined on the entire $x$-$y$ plane $\Bbb R^2$, we may choose $(x_0, y_0) = (0, 0)$ and take $\gamma$ to run from $(0, 0)$ to $(x, 0)$ along the $x$-axis, then from $(x, 0)$ to $(x, y)$ along the segment parallel to the $y$-axis. We thus have

$\phi(x, y) = \int_{(0, 0)}^{(x,0)} (3s^2 - 2) ds + \int_{(x,0)}^{(x, y)} (-2xe^{2s}) ds; \tag{7}$

in the first of these integrals the $y$-component of $X$, $g(x, y)$, does not appear since the path is solely in the $x$-direction; $X \cdot \gamma'(s) = f(x, y)$ along this path component. And $f(x, y)$ does not appear in the second integral for the same reason, with the roles of $x$ and $y$ reversed. Evaluating these integrals, we find that

$\phi(x, y) = (x^3 - 2x) - x(e^{2y} - 1) = x^3 - x - xe^{2y}; \tag{8}$

it is now easy to see that

$\nabla \phi = (f, g)^T = X, \tag{9}$

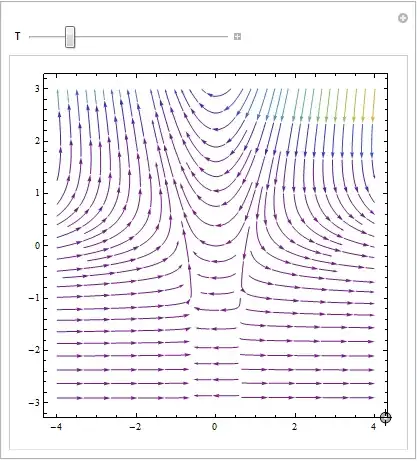

that is, $\phi$ is a potential function for $X$. To see that the trajectories of $X$ are normal to the equipotentials of $\phi$, it is perhaps simplest at this point to observe that since the equipotentials are the curves

$\phi(x, y) = c \tag{10}$

for constant $c$, implicit differentiation of (10) with respect to $x$ yields

$f + gy'(x) = 0, \tag{11}$

which may in fact be written as

$X \cdot (1, y'(x)) = 0, \tag{12}$

and then use the fact that $(1, y'(x))$ is the tangent to the curve $(x, y(x))$, a parametric representation of the equipotential with parameter $x$ itself. This is valid everywhere except where $g(x, y) = 0$, that is, where $x \ne 0$; but it is easy to see that when $g = 0$ we are on the $y$-axis, and there $X$ points in the $x$-direction, so orthogonality of $X$ to the equipotentials holds there as well.

Hope this helps. Happy New Year,

and as always,

Fiat Lux!!!