In optimisation the Newton step is $-\nabla^2f(x)^{-1}\nabla f(x)$. Could someone offer an intuitive explanation of why the Newton direction is a good search direction? For example I can think of steepest gradient decent as a ball rolling down a hill (in three dimensions), I'm struggling to think of a similar analogy for the Newton direction.

4 Answers

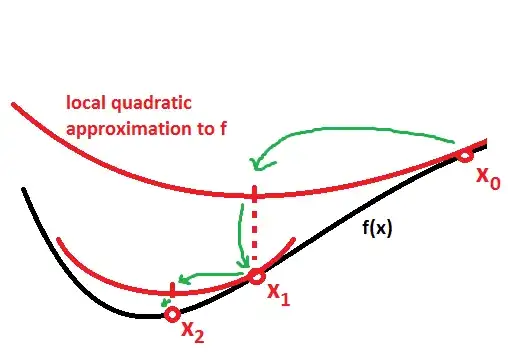

Newton's method in optimization makes a local quadratic approximation of the function based on information from the current point, and then jumps to the minimum of that approximation.

Just imagine fitting a little quadratic surface like a parabola to your surface at the current point, and then going to the minimum of the approximation to find the next point. Finding the direction towards the minimum of the quadratic approximation is what you are doing when you solve, $(f'')^{-1}f'$.

By thinking about this picture, you can also see why Newton's method can converge to a saddle or a maximum in some cases. If the eigenvalues of the Hessian are mixed or negative - in those cases the local quadratic approximation is an upside down paraboloid, or saddle.

- 19,977

In Newton's method we pick $\Delta x$ so that $\nabla f(x_k + \Delta x) \approx 0$. Note that $\nabla f(x_k + \Delta x) \approx \nabla f(x_k) + \nabla^2 f(x_k) \Delta x$. Setting this equal to $0$ and solving for $\Delta x$ gives us the Newton step.

Another viewpoint is to start with \begin{equation*} f(x_k + \Delta x) \approx f(x_k) + \langle \nabla f(x_k), \Delta x \rangle + \frac12 \langle \Delta x, \nabla^2 f(x_k) \Delta x \rangle. \end{equation*} Minimizing the right hand side with respect to $\Delta x$ gives us the Newton step.

- 54,048

Boyd's Convex optimization Chapter 9.5 gives an intuitive way to think about the Newton step in $\mathbb{R}^n$ as the steepest descent direction in the norm of the Hessian.

You can also think of it like this:

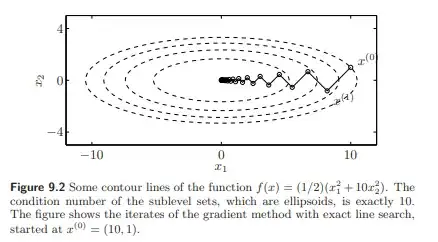

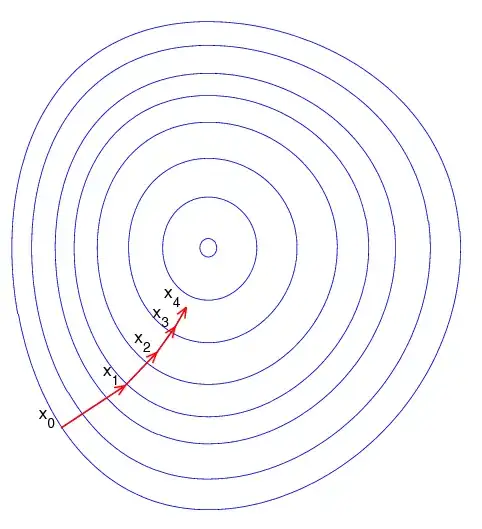

Gradient descent converges the fastest when the gradient $\nabla f$ points towards the minimum $x^*$ of the function. This happens when the function is uniformly "bowlshaped" with its level sets being circles. In these cases, the condition number of the Hessian $\nabla^2 f(x)$ around $x^*$ is $1$.

If your function's level sets are stretched out into ellipses, gradient descent will do poorly by bouncing side to side and only advancing slowly towards the minimum. But you can apply a linear preconditioner $P$ to $x$ $\tilde{x}=Px$ such that the function in the transformed coordinates $f(\tilde{x})$ has a nicer, more uniform bowl shape, giving you a better alignment between the local gradient and the minimizer of the function.

The locally best (and most expensive to compute) preconditioner is the inverse of Hessian at $x$, $\nabla^2 f(x)^{-1}$.

When $x$ is close to $x^*$ it will unstretch the function in the new coordinates to a nice "bowl" shape around the transformed minimum $\tilde{x^*}$ with hessian $\nabla^2 f(\tilde{x^*}) = \nabla^2 f(\tilde{x^*}) \nabla^2 f(\tilde{x})^{-1} \approx I$

- 143

Newton's method for finding zeros of a function $f$ is as follows $$ x_{n+1}=x_{n}-\frac{f\left(x_{n}\right)}{f^{\prime}\left(x_{n}\right)}. $$ For nice enough $f$ and initial guess $x_{0}$, we get that $$ f\left(\lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}x_{n}\right)=0. $$ The animation on https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newton's_method is particularly nice and will help you understand what is happening.

Newton's method in optimization is the same procedure applied to $f^{\prime}$, so that $$ x_{n+1}=x_{n}-\frac{f^{\prime}\left(x_{n}\right)}{f^{\prime\prime}\left(x_{n}\right)}. $$ This allows us to find $$ f^{\prime}\left(\lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}x_{n}\right)=0. $$ In particular, $x_{n}\rightarrow x$ is a critical point.

- 25,738