We do the "opposite directions" and "better approximation" parts, including an estimate of how much better.

We are intended to assume that $m$ and $n$ are positive, and indeed that they are positive integers. In the argument below, we do not need $m$ and $n$ to be integers, but we do assume they are positive. Some assumption needs to be made, since $m=-1$, $n=1$ quickly leads to disaster!

Look at

$$\frac{m+2n}{m+n}-\sqrt{2}.$$

This is equal to

$$\frac{m+2n-m\sqrt{2}-n\sqrt{2}}{m+n},$$

which in turn is equal to

$$-\frac{(\sqrt{2}-1)(m-n\sqrt{2})}{m+n}.$$

Divide top and bottom by $n$. We get that the above expression is equal to

$$-\frac{(\sqrt{2}-1)(\frac{m}{n}-\sqrt{2})}{1+\frac{m}{n}}.$$

So we conclude that

$$\frac{m+2n}{m+n}-\sqrt{2}=\left(-\frac{\sqrt{2}-1}{1+\frac{m}{n}}\right)\left(\frac{m}{n}-\sqrt{2}\right).$$

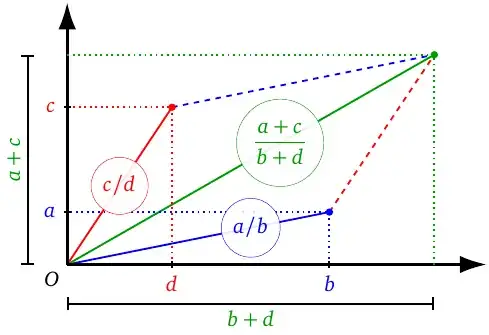

Note that the "multiplication factor" $-\frac{\sqrt{2}-1}{1+\frac{m}{n}}$ is negative. That means that if $\frac{m}{n}-\sqrt{2}$ is negative, then $\frac{m+2n}{m+n}-\sqrt{2}$ is positive, and if $\frac{m}{n}-\sqrt{2}$ is positive, then $\frac{m+2n}{m+n}-\sqrt{2}$ is negative. Thus the approximations alternate between too big and too small.

Note also that the multiplication factor $-\frac{\sqrt{2}-1}{1+\frac{m}{n}}$ has absolute value less than $\sqrt{2}-1$, which is less than $0.5$. So the absolute value of the error when we approximate $\sqrt{2}$ by $\frac{m+2n}{m+n}$ is less than half the absolute value of the error when we approximate $\sqrt{2}$ by $\frac{m}{n}$.

Note that we can make a better estimate of the rate of approach to $\sqrt{2}$, if we assume that we start with $m=n=1$. For then, forever, our approximation will be bigger than $1$, so the multiplication factor has absolute value $(\sqrt{2}-1)/(1+m/n)$, which is less than $(\sqrt{2}-1)/2$.