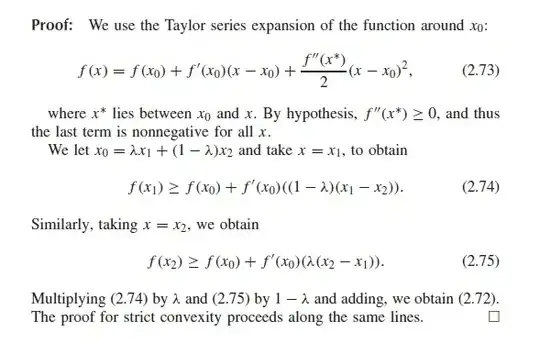

In proof of the following theorem;

If $f$ has a second derivative that is non-negative (positive) over an interval then $f$ is convex (strictly convex). $f$ is in real number space.,

the book I refer, uses Taylor series expansion but disregards terms of order 3 and above. So I'm not convinced of the correctness of the proof, which I paste below. Is there a way to bound the terms of order 3 and above in the follow proof?

I think bounding the error of higher order terms is important in many cases. So would really appreciate a clear answer. Thanks a lot.