It's actually not that hard to compute the two irreducible representations of dimension $3$. Let $\rho$ be such a representation. Since $\rho(a)$ is similar to $\rho(a^2)=\rho(a)^2$, by spectral mapping theorem, the spectrum $\sigma(a)$ of $\rho(a)$ is closed under squaring. If $\sigma(a)=\{1\}$, then $a=I_3$, the representation must be reducible. Therefore $\sigma(a)$ contains a primitive $7$th root of $1$, say $\zeta$, then it also contains $\zeta^2, \zeta^4$ which are all distinct, hence they must be all of $\sigma(a)$. And by $bab^{-1}=a^2$, $\rho(b^{-1})$ sends the eigenspaces $E_{\zeta}, E_{\zeta^2}, E_{\zeta^4}$ to $E_{\zeta^2}, E_{\zeta^4}, E_{\zeta^8}=E_{\zeta}$ respectively. So under $\{v, b^{-1}v, b^{-2}v\}$ for any nonzero $v\in E_{\zeta}$, we have

$$\rho(a) = \begin{pmatrix} \zeta & & \\ & \zeta^2 & \\ & & \zeta^4\end{pmatrix}, \rho(b^{-1}) = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}$$

This must be irreducible, because $\rho(a), \rho(b^{-1})$ don't commute, hence cannot be decomposed as direct sum of one dimensional representations.

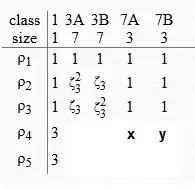

In particular, the last two rows are of the form $[3, 0, 0, *, *]$.

We can compute $x,y$ by picking $\zeta$, but we'd rather finish by orthogonality relations. The orthogonality of 1st and 4th row gives $x+y=-1$. And the inner product of the 4th row with itself gets us $|x|^2+|y|^2=4$.

If one of $x,y$ are real, then by $x+y=-1$, they are both real, moreover

$$\begin{cases} x^2+y^2=4 \\ x+y=-1 \end{cases}\Rightarrow xy=\frac{(x+y)^2-(x^2+y^2)}{2}=-\frac{3}{2}$$

But $x,y$ must be algebraic integers, so must be $xy$.

Thus $x,y$ are both imaginary, and since the Galois conjugate of an irreducible representation is still irreducible, we have the last row ends with $\bar x, \bar y$.

There is an outer automorphism $f$ of $G=\Bbb Z/7\Bbb Z\rtimes\Bbb Z/3\Bbb Z$: $f(a)=a^3, f(b)=b$.

As $\rho_4$ is irreducible, so is $\rho_4\circ f$, hence $\rho_4\circ f$ is isomorphic to $\rho_4$ or $\rho_5$. Since $f$ interchanges the classes $7A$ and $7B$, the character of $\rho_4\circ f$ can be obtained by switching $x,y$. Hence $\rho_4\circ f\simeq \rho_4$ iff $x=y$ which is incompatible with $x+y=-1, |x|^2+|y|^2=4$. Therefore $\rho_4\circ f\simeq \rho_5$, and the last row must end up with $y, x$.

Thus we must have $x=\bar y$, and $|x|^2+|y|^2=4$ implies $xy=2$.

So $$\begin{cases} xy = 2 \\ x+y=-1 \end{cases}\Rightarrow x, y = \frac{-1\pm \sqrt{-7}}{2}$$