Consider the exponential decay curve $y = e^{-x}$, which starts at the point $A = (0,1)$ and approaches the $x$-axis as $x \to \infty$. The total area under this curve from $x = 0$ to $\infty$ is known to be:

$$ \int_0^\infty e^{-x} \, dx = 1. $$

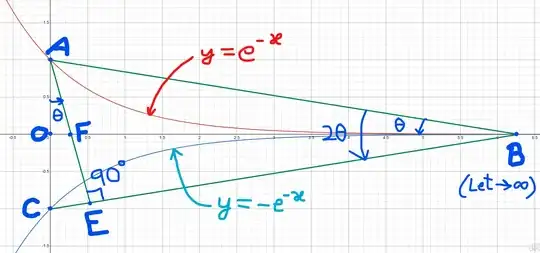

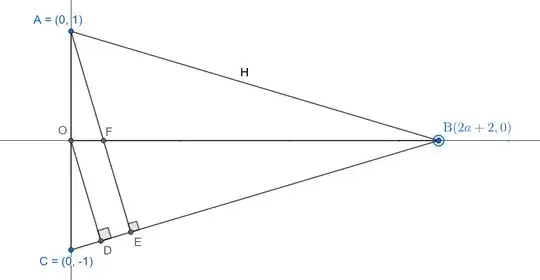

Now, imagine forming a triangle $\triangle AOB$, where:

- $O = (0,0)$ (the origin),

- $A = (0,1)$ (the curve's initial point),

- $B = (\to\infty, 0)$ ,

- and segment $AB$ connects $A$ directly to the tail of the curve, forming a closed triangle.

Let us assume that the area of triangle $AOB$ is the area under the curve (which is 1) plus some extra area $a$. So:

$$ \text{Area}_{\triangle AOB} = 1 + a. $$

Also, since triangle $AOB$ is right-angled at $O$, its area can also be written as:

$$ \text{Area} = \frac{1}{2} \cdot AO \cdot OB = \frac{1}{2} \cdot 1 \cdot OB = \frac{OB}{2}. $$

Equating both expressions for the area:

$$ 1 + a = \frac{OB}{2} \Rightarrow OB = 2a + 2. $$

Let $H = AB$ be the hypotenuse. Then, by Pythagoras Theorem:

$$ H^2 = AO^2 + OB^2 = 1^2 + (2a + 2)^2 = 4a^2 + 8a + 5. $$

Consider a point $C = (0, -1)$ to which we join $B$ and form triangle $\triangle COB$. Now in triangle $ACB$, draw a perpendicular $AE$ onto the base $CB$. Let $AE$ intersect $OB$ at a point $F$.

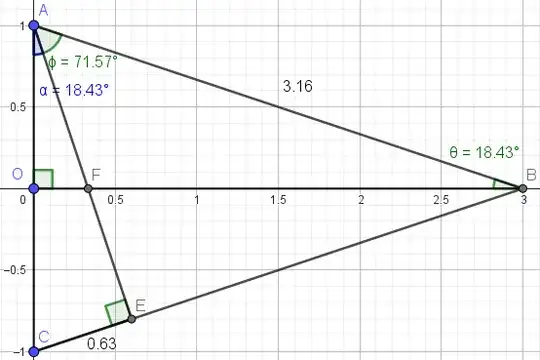

Let $\theta$ be the angle $\angle ABO$. Since triangle $AOB$ is right-angled at $O$, we know:

$$ \angle ABO = \theta, \quad \angle CAB = 90^\circ - \theta. $$

Notice that in triangle $ACB$, $AB=BC$ and therefore:

$$ \angle ABO = \angle CBO = \theta $$ $$ \angle ABC = 2\theta $$

Now observe triangle $AEB$ — the full angle at $A$ becomes:

$$ \angle CAB = \angle CAE + \angle EAB. $$

Also, from triangle $AEB$:

$$ \angle EAB = 90^\circ - 2\theta. $$

So:

$$ \angle CAE = \angle CAB - \angle EAB = 90^\circ - \theta - (90^\circ - 2\theta) = \theta $$

Hence,:

$$ \boxed{\angle CAE = \angle ABO = \theta} $$

Now, using trigonometry in triangle $AOB$:

$$ \sin \theta = \frac{AO}{AB} = \frac{1}{H}. $$

In triangle $ACE$, we also have:

$$ \sin \theta = \frac{CE}{AO+OC} = \frac{CE}{1+1} \Rightarrow CE = 2\sin\theta= \frac{2}{H}. $$

So the small segment $CE$ is known. Now:

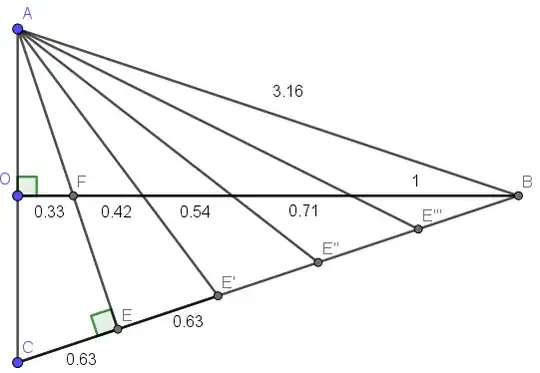

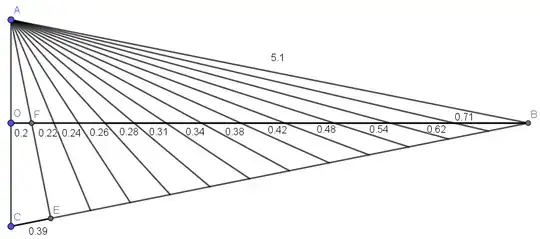

- We project $n$ number of line segments from $A$ onto $CB$ such that they divide $CB$ into equal lengths, each equal to $CE = \frac{2}{H}$.

- The first line segment is the perpendicular $AE$ itself.

- The final line segment is $AB$ that lands on $B$.

- Also observe that these $n$ number of line segments also divide $OB$ into equal lengths, each equal to $OF$.

Hence, the total number of such projections on $CB$ is:

$$ n = \frac{CB}{CE}. $$

But triangle $\triangle ABC$ is isosceles, with $AB = BC = H$, so:

$$ n = \frac{H}{2/H} = \frac{H^2}{2}. $$

Now let’s examine the segment $OB = 2a + 2$, and again recall from triangle $AOB$:

$$ \tan \theta = \frac{AO}{OB} = \frac{1}{2a + 2}. $$

In triangle $AOF$, which is right-angled at $O$, we also have:

$$ \tan \theta = \frac{OF}{AO} = OF/1. $$

Equating both expressions:

$$ OF = \frac{1}{2a + 2}. $$

As discussed before, the $n$ number of projections also divide $OB$ into equal lengths of $OF$. Therefore:

$$ n = \frac{OB}{OF} = \frac{2a + 2}{1/(2a + 2)} = (2a + 2)^2. $$

Equating this to the previous value of $n$:

$$ \frac{H^2}{2} = (2a + 2)^2. $$

We had:

$$ H^2 = 4a^2 + 8a + 5. $$

Substitute:

$$ \frac{4a^2 + 8a + 5}{2} = (2a + 2)^2. $$

Multiply both sides by 2:

$$ 4a^2 + 8a + 5 = 8a^2 + 16a + 8. $$

Bring all terms to one side:

$$ 0 = 4a^2 + 8a + 3 \Rightarrow a^2 + 2a + \frac{3}{4} = 0. $$

Solving:

$$ \boxed{a = -\frac{1}{2}, \quad a = -\frac{3}{2}} $$

But $a$ was introduced as the additional area beyond the area under the exponential curve — hence it must be non-negative.

Therefore, this contradiction suggests that trying to "close" the triangle over the exponential curve leads to negative area, which is geometrically invalid.

And what's more absurd is that if we respectively put these two negative values of $a$ in $OB=2a+2$, we get $OB=+1,-1$, which is impossible since $OB\to\infty$.

Conclusion / Open Question:

Why does this contradiction emerge? Is it because the asymptote at $y = 0$ can never be "closed" into a triangle using finite Euclidean geometry? Or did we just prove that the exponential curve never touches the asymptote?

I'd love to know how others interpret this contradiction geometrically or analytically.