Given 4 non-negative integers $n_1,n_2,n_1^\prime,n_2^\prime$ so that $n_1+n_2=n_1^\prime+n_2^\prime=N$, I have the multinomial coefficient $$ \binom{N}{t_1, t_2, t_3, t_4} $$ where $$ t_1+t_3=n_1\, ,\quad t_2+t_4=n_2\, ,\quad t_1+t_2=n_1^\prime\, , \quad t_3+t_4=n_2^\prime. $$ One can then solve $$ t_2=n_1^\prime-t_1\ge 0\, ,\quad t_3=n_1-t_1\ge 0\, ,\quad t_4=n_2^\prime-n_1+t_1\ge 0 $$ which restricts the values of $t_1$, and expresses all the $t_k$ in terms of $t_1$ and the known $n$'s and $n^\prime$'s. The value of the multinomial coefficient as a function of $t_1$ is then "almost" Gaussian.

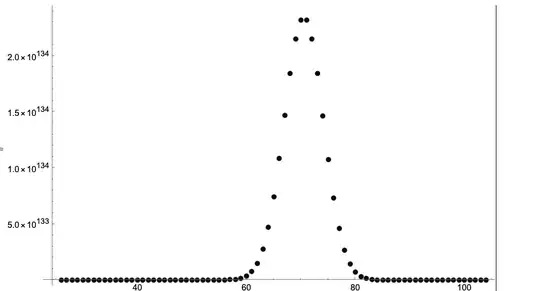

For instance, with $$ N=242\, , n_1=164\, ,n_2=78\, , n_1^\prime =104\, ,n_2^\prime=138\, , $$ we have the following:

where the horizontal axis is $t_1$ and the vertical the value of the multinomial coefficient. The maximum is located at $T_1=71$, although $t_1=70$ is actually numerically very close to the maximum. Without proof, I found this value of $T_1$ to be almost $n_1\times n_1^\prime/N\approx 70.47$ : I can just take the integer part of $n_1\times n_1^\prime/N$ for a very good estimate of this $T_1$, a very convenient expression in terms of the initial data $n_k,n_k^\prime$.

I know from here that $$ \binom{n}{a_1,\ldots,a_k} \sim(2\pi n)^{1/2-k/2}k^{n+k/2}\exp\Big\{-\frac k{2n}\,\sum_{i=1}^k(a_i-n/k)^2\Big\} \tag{1} $$ so subbing $a_i\mapsto t_i$ I obtain (with $k=4$ and $n\mapsto N=242$) $$ \sum_{i=1}^k(a_i-n/k)^2=23747-588 t_1+4t_1^2\\ =4\left(t_1-\frac{147}{2}\right)^2+2138\, . $$ The min of this is reached at $t_1=\frac{147}{2}= 73.5$, which is "not that far" from my guess $n_1\times n_1^\prime/N \approx 70.47$.

Taking various other combinations of $(n_1,n_2,n_1^\prime,n_2^\prime)$ indicates that $n_1 n_1^\prime/N$ is always a better approximation to the location of $T_1$ than starting with Eq.(1). The product $n_1 n_1^\prime /N$ is related to products of Gaussians as per this post

Is there a way to prove the guess $n_1\times n_1^\prime/N$ for the approximate value of $t_1$ that produces the maximum, and is there a systematic way to approximate location of the maximum and the "width" of the Gaussian-like curve in general (for larger $k$) given the initial data, and in particular do so when the $t_i$'s are not independent as in the example given above?