Consider the $\mathfrak{so}_{2n}$ Lie algebra over $\mathbb{C}$, $n\geq 2$. Consider $U=\mathbb{R}^n$, and a basis of $U$ given by the roots

\begin{equation} e_1-e_2,e_2-e_3,\ldots,e_{n-2}-e_{n-1},e_{n-1}-e_n,e_{n+1}+e_n. \end{equation}

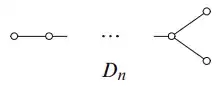

See Brian C. Hall, Lie groups, Lie algebras, and representations. An elementary introduction, Graduate Texts in Mathematics 222, Cham: Springer, pp. xiii+449 (2015), MR3331229, Zbl 1316.22001, page 240 for more details. The associated Dykin diagram is

However, I struggle to understand how the last vertex with an angle arise. The rule I use to construct a Dynkin diagram (see definition $8.31$ in Lie Groups, Lie Algebras, and Representation) do not describe the construction of such diagrams, but it seems to me they would only describe diagrams with vertices on a straight line, such as the one for $A_n$, $B_n$ or $C_n$.