There was a question here a while ago about finding a positive integer sequence $a_n$ such that $\sin(a_n)$ converges. I saw somebody mention in the comments that you can find a sequence $a_n$ such that $\sin(a_n)$ monotonically tends towards $1$. I have no doubt that such a sequence exists, since there's this thread showing that $\sin(a_n)$ for $a_n=n$ is dense in $[-1,1]$, so there's obviously some subsequence you can pick out that's monotonic. However, is there any established formula for this? My intuition is leading me towards a no; if this sequence exists, the first few numbers are going to be $$a_1=1,a_2=2,a_3=8,a_4=14,a_5=33,...$$ I started questioning why $\sin(33)=0.999911...$ was so close to $1$, and realized that $33$ is peculiarly close to $\frac{21}{2}\pi$. I did the math and figured this is because $33 = \frac{21}{2} \cdot \frac{22}{7}$, one of the convergents of $\pi$'s continued fraction. But then, what about the earlier terms? What about $\frac{333}{106},\frac{355}{113}$, etc.?

Also, just as a bit of extra info, I calculated all the terms of this sequence that are lower than $10000$ in Python, and got this:

$$[1,2,8,14,33,322,366,699,1409,2119,2829,3539,4249,4959,5669,6379,7089,7799,8509,9219,9929]$$

Bizarrely, most of this sequence is such that the difference between consecutive terms is 710. Probably has something to do with $\frac{355}{113}$, since that's $355\cdot 2$.

So, to write my question down formally,

I am searching for a sequence $a_n$ such that $a_n \in \mathbb{Z}^+$ and $a_{n+1}$ is the smallest integer such that $\sin(a_{n+1})>\sin(a_n)$ $\forall \ n$. I suspect that this sequence is related to the $n$th convergent to $\pi$'s continued fraction. Is this suspicion correct, how are the two related, and is there a way to calculate the error in $1-\sin(a_n)$?

Thanks for the help!

Edit: some more testing with code virtually confirms that something fishy is going on with this sequence and the continued fraction for $\pi$. Define $b_n = a_{n+1}-a_n$. Then, $$b_1=1,b_2=6,b_3=6,b_4=19,b_5=289,b_6=44,b_7=333,b_8=710,b_9=710...$$ $$...b_{76}=710,b_{77}=104703$$ First off, what the heck's going on with $b_6$ where it's the only term that decreases? Second, $104703=103993+710$, and 103993 is the numerator of the fifth convergent to $\pi$. Can someone figure out what the relation between these two is?

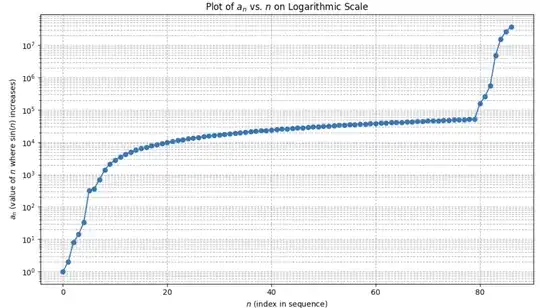

Edit 2: After some testing, the difference $a_{n+1}-a_n$ seems to stay constant for random amounts of time until suddenly jumping to the next numerator of $\pi$ convergents. What are these intervals?? For reference, I've attached a graph of $a_n$ versus $n$ below:

$a_n$ vs $n$" />

$a_n$ vs $n$" />

A line of constant slope gets bent into a logarithmic shape due to the logarithmic scale (the graph is completely unreadable using regular scale). It's starting to look like another stretch of constant $a_{n+1}-a_n$ is developing at the right, but I can't confirm this because my online compiler can't handle searching for values above $5\cdot 10^7$ very well.