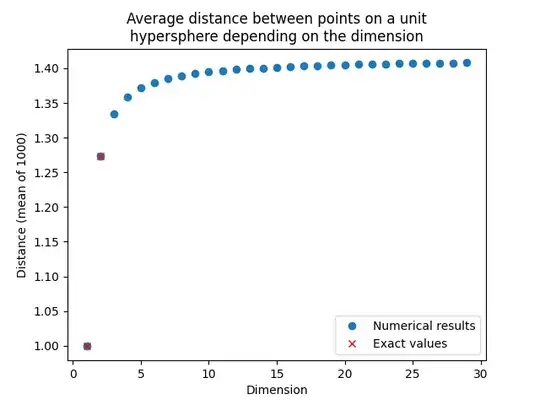

Take the surface of the unit hypersphere of dimension $n$: $$ S = \{x\in\mathbb{R}^n: \lVert x \rVert = 1\} $$ Given two uniformly sampled points on its surface, what is the expected distance between them? And how does the distance scale with the radius? To clarify, I'm asking about Euclidean distance, not along a great circle. This question already answers the question for great circles in any dimension. I made this numerical experiment, which might suggest that the limit is $\sqrt 2$:

Here is the code if you want to try it yourself:

import numpy as np

from scipy.spatial.distance import cdist

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def random_on_unit_hypersphere(dim: int, n: int = 1) -> np.ndarray:

mean = np.zeros(dim)

cov = np.identity(dim)

result = np.random.multivariate_normal(mean, cov, size=n)

norm = np.linalg.norm(result, axis=1)[:, None]

return result / norm

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.set(title='Average distance between points on a unit\nhypersphere depending on the dimension',

xlabel='Dimension', ylabel='Distance (mean of 1000)')

dims = np.arange(1, 30)

means = []

for dim in dims:

# Randomize 1000 points uniformly on the hypersphere of dimension dim.

points = random_on_hypersphere(dim, n=1000)

# Get the matrix where distances[i, j] == np.linalg.norm(points[i] - points[j]).

distances = cdist(points, points)

# The matrix is symmetric, so only take the mean of the values from the upper triangle.

upper_triangle_indices = np.triu_indices_from(distances, k=1) # k=1 means 1 above the diagonal

unique_distances = distances[upper_triangle_indices]

means.append(np.mean(unique_distances))

ax.plot(dims, means, 'o', label='Numerical results')

ax.plot([1, 2], [1.0, 4/np.pi], 'x', color='red', label='Exact values')

ax.legend()

plt.show()