From this question we have the following.

If $n$ persons are randomly allocated to $q$ rooms, then the probability of having exactly $m$ rooms with each exactly $k$ persons is given by

$$ \large p(n,q,m,k) := \frac{1}{q^n}\sum_{j=m}^{\min(q, \left\lfloor \frac{n}{k} \right\rfloor)} (-1)^{j-m} \binom{j}{m} \binom{q}{j} \binom{n}{jk} \frac{(jk)!}{(k!)^j}(q-j)^{n-jk}. $$

My question is:

For given $q,m,k$ what is the $n$ that maximizes $p$?

In another words: how many people should we put in the $q$ rooms to maximize the probability that there are exactly $m$ rooms containing exactly $k$ persons?

(Possibly another question: what if we're also allowed to vary $q$.)

My try: If we let $X$ be the number of rooms with exactly $k$ persons, then (using indicator random variables and linearity)

$$ \mathbb{E}[X] = q \binom{n}{k} (q-1)^{n-k} q^{-n} $$

and in order to maximize $\mathbb{P}(X=m)$, heuristically we should have $\mathbb{E}[X] \approx m$. If we approximate $\binom{n}{k}$ by $\frac{1}{k!} n^k$, we get the equation

$$ n^k \left(1-\frac{1}{q}\right)^n = \frac{k! m(q-1)^k}{q} $$

to which Wolfram Alpha gives a solution in terms of the Lambert-W function

$$ n = \frac{k}{\log(1-1/q)} W\left( \frac{1}{k} \log(1-1/q) \left( \frac{k!m}{q} \right)^{1/k} \right) \tag{1}. $$

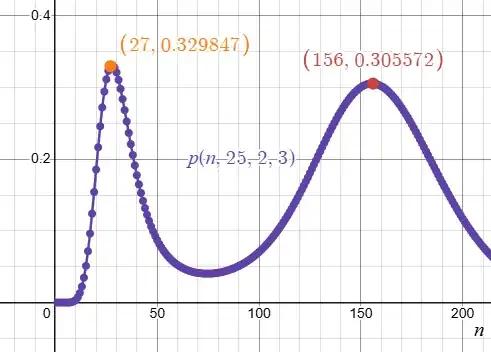

For large $q$ this seems to agree with numerical experiments. The function $n \mapsto p(n,q,m,k)$ appears to have two peaks. The first one approximately given by (1) and the second one (it seems) if we use $W_{-1}$, another branch of the Lambert-W function. But it also looks like the first one is always bigger.