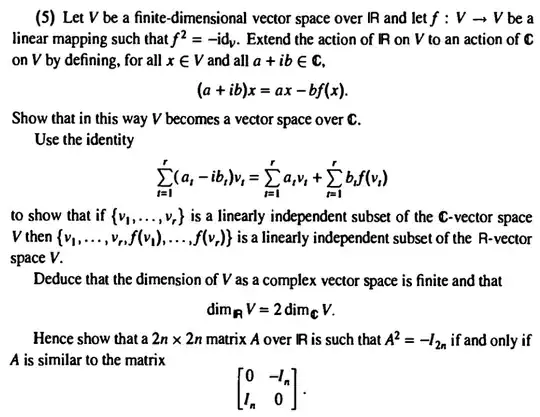

I am trying to answer the end of the following problem:

Specifically: If $A^2=-I_{2n}$, then $A$ is similar to $\begin{bmatrix} 0& -I_n \\ I_n & 0 \end{bmatrix}$.

I tried the following: Applying $f$ in the given basis, we have:

$$\begin{array}{rcl} f(v_1) & = & 0 v_1 + \dots + 0 v_n + f(v_1)+ \dots + 0f(v_n) \\ & \vdots & \\ f(v_n) & = & 0 v_1 + \dots + 0 v_n+0f(v_1)+ \dots + f(v_n) \\ f(f(v_1)) & = & - v_1 + \dots + 0 v_n+0f(v_1)+ \dots + 0f(v_n)\\ & \vdots & \\ f(f(v_n)) & = & 0 v_1 + \dots + - v_n+0f(v_1)+ \dots + 0f(v_n)\\ \end{array}$$

Considering $A^t$ as the matrix of coefficients of the previous system we have that $A=\begin{bmatrix}0& -I_n \\ I_n & 0 \end{bmatrix}$. Applying $f$ again, we see that $A^2=-I_{2n}$. Here we can see that if we reorder the basis - say switching $v_i$ by $v_j$ - we produce a similarity between $A$ and the new matrix of coefficients $B$. Where $B$ is $A$ with rows $i,j$ exchanged and $i,j$ columns exchanged. This seems to suggest that whatever other matrices $B$ that obey $B^2=-I_{2n}$ can be obtained with $A$ by adequate elementary operations on rows and columns.

The trouble for me is the following: This construction where we obtained $A$ seems to rely on $f$ and the basis $\{v_1,\dots,v_n, f(v_1),\dots,f(v_n)\}$ how can we guarantee that there isn't a different linear transformation and a different basis where we obtain matrix $B$ such that $B^2=-I_{2n}$ but $B$ is not similar to $A$?

$$M=\begin{bmatrix} 0&-I_n \ I_n& 0 \end{bmatrix}$$

We have the map $f_M$ defined as $x\mapsto Mx$ which is represented as $M$ in the standard basis. Using theorem $7.5$, the matrix of this mapping relative to another basis will be $A=P^{-1}MP$ for some suitable $P$ and hence $A,M$ are similar. We know that $M^2=-I_{2n}$, we need to check if that is also the case for $A$, with a simple calculation, we see that:

$$A^2=(P^{-1}MP)(P^{-1}MP) = P^{-1}M^2P=P^{-1}(-I_{2n})P=-I_{2n}$$

Is this correct?

– Red Banana Mar 20 '25 at 15:51