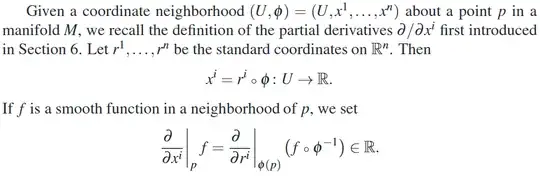

In Tu's manifold book, there is this passage when introducing tangent spaces

I tried to construct an explicit case with $S^2$. Let's say we have a coordinate chart $(U, \varphi)$ where $U=S^2\setminus{\{\text {poles}\}}$, and $\varphi$ is an angular coordinate chart $\theta = [0, 2\pi)$, $\phi = (0, \pi)$ shown below

Let's also say I have some embedding $i:S^2\mapsto \mathbb R^3$ given by $i(\theta,\phi) =(\cos\theta\sin\phi, \sin\theta\sin\phi, \cos\phi)$.

I want to calculate what the basis vectors would look like in the embedded $S^2$ for the tangent space located at $p=(\theta,\phi) = (0, \frac\pi2)$. If I remember correctly, I can do this by applying the "partial derivative" representation of the basis vectors (as seen in the Tu book) to the embedding(?), so something like this $$\left.\frac{\partial}{\partial x^i}\right|_p i= \left.\frac{\partial}{\partial r^i}\right|_{\varphi(p)} i$$

but I am very confused on how to proceed, especially what the difference between $x^i$ and $r^i$ would be in this context.

If I just proceed and assume either one of $x^i,p$ or $r^i,\varphi(p)$ is $\theta,\phi$ and $\left(0, \frac\pi2 \right)$ in the coordinate chart and work out the math, it works

\begin{align*} \vec{v}_\theta & = \left\langle \left.\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}\left[ \cos(\theta)\sin(\phi) \right]\right|_{\left(0, \frac{\pi}{2}\right)}, \left.\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}\left[ \sin(\theta)\sin(\phi) \right]\right|_{\left(0, \frac{\pi}{2}\right)}, \left.\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}\left[ \cos(\phi) \right]\right|_{\left(0, \frac{\pi}{2}\right)} \right\rangle = \langle 0, 1, 0\rangle \\ \vec{v}_\phi & = \left\langle \left.\frac{\partial}{\partial\phi}\left[ \cos(\theta)\sin(\phi) \right]\right|_{\left(0, \frac{\pi}{2}\right)}, \left.\frac{\partial}{\partial\phi}\left[ \sin(\theta)\sin(\phi) \right]\right|_{\left(0, \frac{\pi}{2}\right)}, \left.\frac{\partial}{\partial\phi}\left[ \cos(\phi) \right]\right|_{\left(0, \frac{\pi}{2}\right)} \right\rangle = \langle 0, 0, -1\rangle \end{align*}

but I have no idea why it works.

Also, they both are also interpreted as functions/maps, with $x^i:U\mapsto \mathbb R$ (e.g. $x^2(p) = \frac\pi2$) and $r^i:\mathbb R^n\mapsto\mathbb R$ (e.g. $r^3(a, b, c) = c$), so in a sense we are taking partial derivatives with respect to functions??? What am I misunderstanding.