The obvious evidence that $1\ \mathrm{rad}^2 = 1\ \mathrm{sr}$

is from the Wikipedia article on the steradian:

The steradian (symbol: sr) or square radian[1][2] is the unit of solid angle in the International System of Units (SI).

There it is: steradian and square radian are the same thing.

Units, after all, are what they are because they are defined that way.

You might not believe Wikipedia. Good for you; the contents of an article just depend on who edited it last.

But the idea that a steradian is a square radian is fairly common,

showing up here, here, here, and here.

I also found one source that confusingly first states that

$$

1 \ \mathrm{steradian\ (sr)} = 1 \ \mathrm{square\ radian}\ (\mathrm{rad}^2)

$$

and then that

$$

1 \ \mathrm{square\ radian}\ (\mathrm{rad}^2)

= \mathrm{approximately}\ 1.2732\ \mathrm{steradians\ (sr)}.

$$

No reason is given for the second equation.

The usual intuition behind units such as "square meter" is that you can imagine constructing a square of side one meter in a plane. There is essentially only one way to do this: every such square that you construct is congruent to every other such square. We then define the area of that square as one square meter, $1\ \mathrm m^2.$

The difficulty with defining a "square degree" or "square radian" is that there is no obviously unique and correct way to define a solid angle that is "square."

For ordinary angles in a plane, one radian is the angle subtended at the center of a circle by an arc of length equal to the circle's radius. Equivalently, an angle of measure $\theta$ radians covers an arc of length $\theta$ times the circle's radius on a circle centered at the vertex of the angle.

In analogy to the definition of the radian, a cone whose solid angle is $S$ steradians covers a spherical region of area $S$ times the square of the sphere's radius on a sphere centered at the apex of the cone.

Equivalently, a region on a sphere of area $S$ times the square of the sphere's radius subtends a solid angle of $S$ steradians at the center of the sphere.

The example of a right circular cone given on the Wikipedia page is just an example of a solid angle. The region on the sphere covered by the solid angle can be any sufficiently simple shape, as mentioned later on the same page, just as the area of a region of any sufficiently simple shape in the plane can be defined in square units.

Defining a steradian in terms of a right circular cone is like defining a square meter in terms of a circle. A circle of area $1\ \mathrm m^2$ has a radius of $\dfrac{1}{\sqrt\pi}\ \mathrm m$ and a diameter of $\dfrac{2}{\sqrt\pi}\ \mathrm m,$

neither of which is one meter. The diameter of this circle is analogous to the aperture of the cone described in the Wikipedia article.

On that basis, we can dismiss that particular piece of "evidence"; it is irrelevant to the question of whether $1\ \mathrm{rad}^2 \stackrel?= (1\ \mathrm{rad})^2.$

The square degree is a little easier to conceive than a square radian because you can construct a square pyramid such that the angles between adjacent edges at the apex of the cone are all one degree, and this pyramid will cover a region on the sphere whose area is approximately one square degree. But it's not an exact construction of a square degree, because even at that scale you cannot really construct a square on the surface of a sphere. It is, again, merely a somewhat reasonable approximation of a square.

To be exact, the solid angle at the apex of a square pyramid of apex angle $1$ degree is (according to Wikipedia)

$$ 4 \arcsin\left(\sin^2\left( \frac{\pi}{360} \right)\right)\ \mathrm{sr}

= 0.00030460968751\ldots\ \mathrm{sr}

$$

whereas a square degree is $\left(\frac\pi{180}\right)^2$ steradians, and

$$

\left(\frac\pi{180}\right)^2\ \mathrm{sr}

= 0.0003046174197867\ldots\ \mathrm{sr}.

$$

As you can see, these results don't even agree to five significant digits.

To be clear, there are places where someone says a square degree is the solid angle of a square pyramid with apex angle $1$ degree. They can do that partly because the square degree is not a standard unit of measurement, and partly because they are using the square degree for applications where three or four significant digits is plenty of precision.

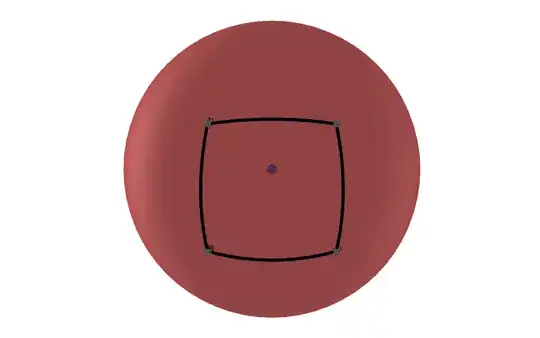

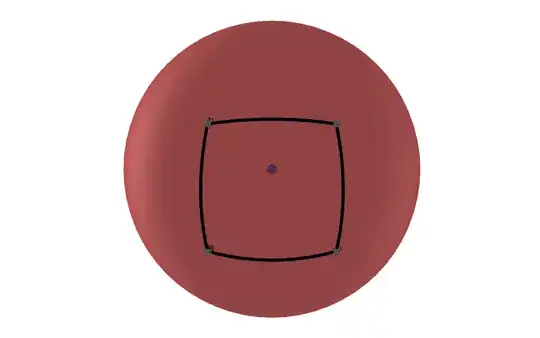

If you open up the apex angle of the square pyramid to $1$ radian,

the area it intercepts on the sphere is even less like a square.

It looks like the region outlined on the sphere below:

This region is $1$ radian across from the midpoint of one side to the midpoint of the opposite side. But we usually measure squares by the length of their edges, and the edges of this shape are much less than one radian.

Moreover, none of the angles at the vertices is a right angle.

You can't do the usual things you can do with a square to illustrate how area works, such as putting four of these shapes together to make a "square" of twice the size and four times the area.

We could alternatively enlarge the angles of the pyramid so that the edges of this region all measured $1$ radian, but then the width would be greater than $1$ radian and none of the other problems would be solved.

The problem with the pyramid is that it doesn't really create a solid angle in the shape of a square. Maybe you could call its solid angle the pyramidal radian instead of a square radian; that would avoid at least some confusion.

For the question of whether $1\ \mathrm{sr} = 1\ \mathrm{rad}^2,$

we first have to accept that $\mathrm{rad}^2$ can be a unit of solid angle measure.

There are rules for conversions between quantities when the quantities are expressed in square units: if the units u and v are related by

$1\ \mathrm{u} = k\ \mathrm{v},$

then the corresponding squares of units are related by

$1\ \mathrm{u}^2 = k^2\ \mathrm{v}^2.$

Since $1\ \mathrm{rad} = \dfrac{180}{\pi}\ \mathrm{deg},$

therefore $1\ \mathrm{rad}^2 = \left(\dfrac{180}{\pi}\right)^2\ \mathrm{deg}^2.$

If we accept $\mathrm{deg}^2$ as a measure of solid angle defined such that

$1\ \mathrm{sr} = \left(\dfrac{180}{\pi}\right)^2\ \mathrm{deg}^2,$

it follows that $\mathrm{rad}^2$ also is a measure of solid angle and that

$1\ \mathrm{rad}^2 = 1\ \mathrm{sr}.$

Note, however, that square degrees are a non-SI unit and that this is all therefore non-standard with regard to SI.

The real difficulty in saying whether

$1\ \mathrm{rad}^2 \stackrel?= (1\ \mathrm{rad})^2$

is in deciding what it means to multiply a measurement by itself.

One might imagine that constructing a square of side $1\ \mathrm m$ is somehow "multiplying" the length of the side by itself.

Personally, I'm not convinced. You can relate the square to multiplication by showing how rectangles of various side lengths have areas in proportion to the numbers you get by multiplying the number of units of length on each side, but that's not the same thing as showing that constructing a rectangle or square is multiplication.

But what does it mean to multiply one second by itself?

What does it mean to multiply one kilogram by itself?

"Square seconds" show up in measurements of acceleration and "square kilograms" show up in the gravitational constant, but we can hardly construct a square of side one second or one kilogram except in a highly artificial way.

Constructing a square with a side equal to the given unit is something that can only really be done with units of length.

So I end with a frame challenge. What is the meaning of

$(1\ \mathrm{rad})^2$?

In support of that frame challenge, the fact that there is a separate definition for steradians in SI rather than simply measuring solid angles in $\mathrm{rad}^2$ might be reason to reconsider whether "square angle" is really a way to measure solid angles at all.