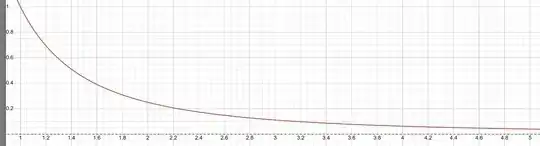

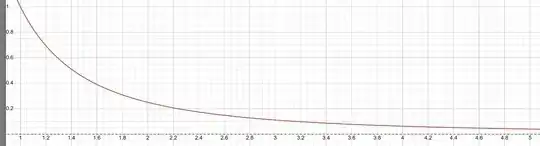

The approximation

$$ L = \int_{x=1}^\infty \frac{1}{x^2} = \left[ -\frac{1}{x}\right]^\infty_1 = 1$$

actually undercounts the true area of

$$ \sum_{x=1}^\infty \frac{1}{n^2}$$

Adding the sum of all the triangular deficits

$$ T = \frac{f(1)-f(2)}{2} + \frac{f(2)-f(3)}{2} + \frac{f(3)-f(4)}{2} + ...= \frac{f(1)}{2}= \frac{1}{2}$$

so that

$$ \sum_{x=1}^\infty \frac{1}{n^2} \approx L + T = 1 + \frac{1}{2} = 1.5$$

which still undercounts the true area by a small crescent shaped summation.

E.g. area of the first crescent between $x=1$ and $x=2$ is area of the trapezoid minus area under the integral

$$ A_1 = \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{1}{1^2} + \frac{1}{2^2}\right) - \left(\frac{1}{1} -\frac{1}{2} \right) = \frac{5}{8} - \frac{1}{2} = \frac{1}{8}$$

In general

$$A_n = \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{1}{n^2} + \frac{1}{(n+1)^2}\right) - \left( \frac{1}{n}-\frac{1}{n+1} \right) = \frac{1}{2n^2(n+1)^2}$$

Therefore the infinite sum of all cresents:

$$A = A_1 + A_2 + A_3 + ...$$

exactly accounts for the remaining area deficit.

Hence

$$\sum_1^\infty \frac{1}{n^2}= L + T + A$$

$$= 1 + \frac{1}{2} + \sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{1}{2n^2(n+1)^2}$$

which converges termwise as $O(\frac{1}{n^4})$ faster than the original $O(\frac{1}{n^2})$.

Further convergence acceleration may be achieved by splitting

$$\sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{1}{2n^2(n+1)^2}$$

into easily calculated boundary terms $+$ an even faster converging infinite sum.

Euler used the same general method to carve away successive boundary terms using integration by parts. Starting with

$$A_1 = \frac{f(0)+f(1)}{2} - \int_0^1 \color{blue}{1} \cdot \color{green}{f(x)} dx$$

Integrating by parts using $u = \color{green}{f(x)}$ and $dv = \color{blue}{1 \cdot dx}$,

$$A_1 = \frac{f(0)+f(1)}{2} - \left[f(x)(x+c)\right]_0^1 + \int_0^1 (x+c) f^1(x) dx$$

Since $c$ may take on any value, choosing $c=-\frac{1}{2}$ gives

$$A_1 = \frac{f(0)+f(1)}{2} - \frac{f(1)+f(0)}{2} + \int_0^1 \left(x-\frac{1}{2}\right) f^1(x) dx$$

$$= \left[f^1(x) \left(\frac{x^2}{2}-\frac{x}{2}+ c\right)\right]_0^1 - \int_0^1\left(\frac{x^2}{2}-\frac{x}{2}+ c\right)f^2(x)dx$$

Choosing $c=\frac{1}{12}$,

$$=\frac{f^1(1)-f^1(0)}{12} - \int_0^1\left(\frac{x^2}{2}-\frac{x}{2}+ \frac{1}{12}\right) f^2(x)dx$$

$$=\frac{f^1(1)-f^1(0)}{12} - \left[f^2(x)\left(\frac{x^3}{6}-\frac{x^2}{4}+ \frac{x}{12}+c\right)\right]_0^1 + \int_0^1 \left(\frac{x^3}{6}-\frac{x^2}{4}+ \frac{x}{12}+c\right) f^3(x)dx$$

Choosing $c=0$,

$$=\frac{f^1(1)-f^1(0)}{12} + \int_0^1 \left(\frac{x^3}{6}-\frac{x^2}{4}+ \frac{x}{12}\right) f^3(x)dx$$

$$=\frac{f^1(1)-f^1(0)}{12} - \left[f^3(x)\left(\frac{x^4}{24}-\frac{x^3}{12}+ \frac{x^2}{24} + c\right)\right]_0^1 + \int_0^1 \left(\frac{x^4}{24}-\frac{x^3}{12}+ \frac{x^2}{24} + c\right) f^4(x)dx$$

Choosing $c=-\frac{1}{720}$,

$$=\frac{f^1(1)-f^1(0)}{12} - \frac{f^3(1)-f^3(0)}{720} + \int_0^1 \left(\frac{x^4}{24}-\frac{x^3}{12}+ \frac{x^2}{24} + c\right) f^4(x)dx$$

$$\approx \frac{f^1(1)-f^1(0)}{12} - \frac{f^3(1)-f^3(0)}{720}$$

ending the approximation.

Since

$$A_1 \approx \frac{f^1(2)-f^1(1)}{12} - \frac{f^3(2)-f^3(1)}{720}$$

$$A_2 \approx \frac{f^1(3)-f^1(2)}{12} - \frac{f^3(3)-f^3(2)}{720}$$

$$A_3 \approx \frac{f^1(4)-f^1(3)}{12} - \frac{f^3(4)-f^3(3)}{720}$$

$$.$$

$$.$$

By telescoping,

$$\sum_i^\infty A_i \approx - \frac{f^1(1)}{12} + \frac{f^3(1)}{720}$$

and since

$$ \left[f^1\left(x\right) = -\frac{2}{x^3} \right]_1 = -2$$

$$ \left[f^3\left(x\right) = -\frac{24}{x^5} \right]_1 = -24$$

Therefore

$$ \sum_1^\infty \frac{1}{n^2} = L + T + A \approx 1 + \frac{1}{2} +\frac{1}{6} -\frac{1}{30} = 1.6 \dot 3 $$