Let $F:U\to V, U, V$ bounded open subsets of $\mathbb{R}^n,$ be a homeomorphism. We don't assume diffeomorphism. I think my question is related to this question, this question, this question, and this question.

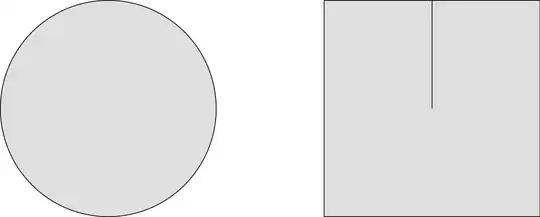

Since $U,V$ are bounded, they have non-empty boundaries in $\mathbb{R}^n.$ Can we always say that the homeomorphism $F$ extends to a homeomorphism of the closure, again (by abusing notation) denoted by $F,$ so that $F(\partial U)=\partial V?$ I think the answer is no, but I'm having trouble finding a simple counterexample.

Here's how I'm thinking about it:

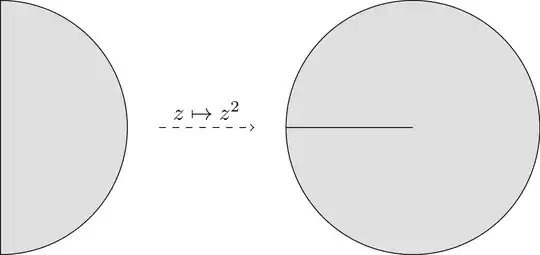

Let $u\in \partial U \implies u_n \in U, u_n \to u.$ Consider $L:=\{F(u_n)\} \subset V,$ which is bounded. So $L$ has a convergent subsequence $\{u_{n_k}\}$ converging to a limit point $v \in \bar{V}.$ But $v\notin V$, because if so, then the subsequence $\{u_{n_k}\}\to F^{-1}(v)\in U,$ contradicting the fact that $\{u_{n_k}\}\to u\in \partial U,$ assumed earlier. So $v \in \partial V.$

The above argument shows that any limit point or cluster/accumulation point of $L$ must lie in $\partial V.$ What it does not prove is that the limit point set of $L$ is a singleton set. So this seems like an obstacle in proving that $F$ maps boundary to boundary.

If limit point set of $L$ was indeed singleton, then we'd have: $F(u_n)\to v \in \partial V.$ I feel this also means $v$ must be equal to $F(u),$ but can't get my argument sorted (pretty sure I'm missing something obvious!). If $F$ is continuous up to the boundary, then of course $v=F(u).$ But is it still so if $F$ is not continuous up to the boundary? Maybe some help is useful here. I think that in a potential counterexample, the limit points of $L$ will not be unique...