I am trying to come up with an example of a group $G$ which has 2 elements (maybe the group itself has more elements) s.t. $g,h\in G$, and $o(h)=o(g)=3$, but $o(gh)=2$. Clearly it is not an Abelian group. I am trying to avoid using group presentations and relations, just trying to find one concrete example for it, or if it does not exist, a hint as to why it is the case.

-

1Does not work with S3. You have 2 elements of order 3 but their product is the identity – User666x Feb 22 '25 at 13:45

-

3It's unfortunate Shaun deleted his answer. The "freeest" group generated by such elements is $A_4$, and no proper quotient of $A_4$ has this property. Thus any group containing two such elements, those elements will generate a subgroup isomorphic to $A_4$. – Steve D Feb 22 '25 at 23:11

4 Answers

Alternating group $A_4$ would be one example. You can set $g=(1\ 2\ 3)$ and $h=(1\ 4\ 3)$ and you will get $gh=(1\ 4)(2\ 3)$. And since we know that the order of element of permutation group is equal to lcm of lengths of their cycles you'll get your conditions satisfied.

- 63,683

- 4

- 43

- 88

- 2,709

The general question of "given $\ell, m, n\geq1$, can I find a non-trivial group with elements $g$, $h$ and $gh$ of these orders" has been asked and answered a few times here. They give a different view of the problem, and pointing to them in abstraction is not immediately helpful here given that the answer is "$A_4$". However, here are two general methods:

- A representation theory/matrix approach, in this answer of Derek Holt.

- A geometric approach, in this answer of mine.

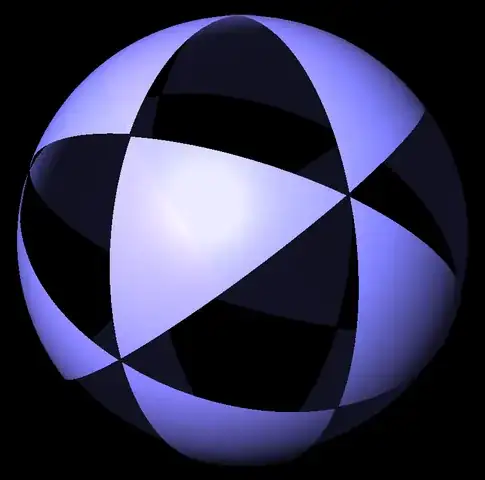

The geometric approach is simply to show that the orientation-preserving* group of symmetries of the following triangulation of the sphere has the properties you require. Each triangle has angles $\pi/3, \pi/3, \pi/2$.

The underlying theory of triangle groups/von Dyck groups shows that a similar tessellation of triangles can be found for any triple $(\ell, m, n)$, each $\ell, m, n>1$. This will be a tessellation of the sphere, or of the real plane, or of the hyperbolic plane. Therefore, no matter which $3$ numbers chosen, you can always find a non-trivial group with $o(g)=\ell, o(h)=m, o(gh)=n$. See the post I linked to above or wikipedia for more details.

*i.e. translate, don't reflect

- 32,369

You directly mentioned avoiding group presentations and relations, but that framework gives an answer so straightforward that I feel like I have to give it. You're asking for a group $G$ with a subgroup isomorphic[1] to the group generated by the following presentation:$$\langle{g,h\mid g^3=h^3=(gh)^2=1}\rangle.$$Suspecting this is a finite group, we can just plop this into SageMath / GAP to figure out its structure. For example, I wrote this code:

F = FreeGroup(2)

g,h = F.gens()

G = F.quotient([g^3, h^3, (g*h)^2])

G.gap().StructureDescription()

The output is A4, the alternating group in $4$ elements. This means that you are asking for a $G$ with a subgroup isomorphic to $A_4$. To get a list of such groups ordered by size, we can consult the LMFDB.

[1] This is technically incorrect; your question asks for a quotient of the free group on 2 generators by at least these relations, and we could have added more relations. Now that we know what group it is, we can enumerate all of its quotients to figure out all possible subgroups generated by 2 elements that meet your criteria. In the LMFDB we can see that $A_4$ has only one nontrivial quotient, $C_3$.

- 780

-

2+1, although I feel that the first paragraph is overly hopeful - you cannot just put relations like $g^3$ and $(gh)^2$ in a presentation and trust that the elements will have order $3$ or $2$ or whatever. For example, $\langle g, h\mid g^2, h^3, gh^{-1}\rangle$. So proving that your group actually has this property is super-important (and of course this is what your bit starting "suspecting" is doing). – user1729 Feb 25 '25 at 19:55

-

1@user1729 Sure, though also if there had been hidden cancellation like that the code would have still answered OP's question by proving no such pairs exist. – Joshua P. Swanson Feb 25 '25 at 20:24

-

@user1729 Yes, rather than "the answer is straightforward", it would be more apt to say "we can do some straightforward checks that might answer the question". – L. E. Feb 25 '25 at 22:19

-

@JoshuaP.Swanson This only works almost by chance. Similar problems fail, and for example it is an old open problem of Magnus whether one can algorithmically determine if there is a non-trivial group on $n$ generators which satisfies $n$ given rules on those generators (i.e. it is unknown if there is an algorithm to determine if a balanced presentation defines a non-trivial group). – user1729 Feb 26 '25 at 09:24

-

@user1729 Well, this case is simple enough that I took it as a matter of course that GAP would be about to figure out the quotient group in an understandable way. I was just noting that as long as one can read off the orders of g,h,gh from its output, you'll definitely have an answer to the original question. Certainly you can give innocuous-looking presentations that are extremely complicated, maybe impossible, to handle. – Joshua P. Swanson Feb 26 '25 at 11:33

More strongly, for any integer $m, n, r>1$, there exists a finite group $G$ and $a, b\in G$ such that the orders of $a, b, ab$ are $m, n, r$, respectively. For a proof, see Theorem 1.64 of these course notes of Milne.

- 92,241

- 479