Consider an $n$ by $n$ square subdivided into unit squares. What is the shortest path you can take through the square that touches every unit square? Touching the edges/vertices of the squares is sufficient, the path can be of any shape, with any start and end point.

For $n < 3$ the answer is trivially $0$.

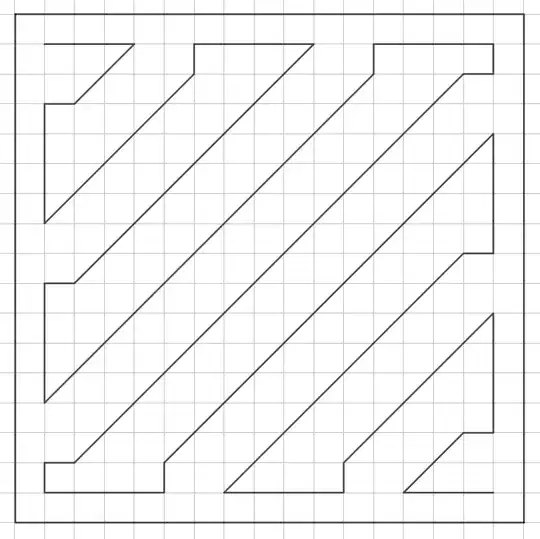

We want to maximize the # of diagonals and minimize the # of orthogonal moves as $\frac{3}{\sqrt{2}}>\frac{2}{1}$, thanks to @Zoe Allen for pointing this out.

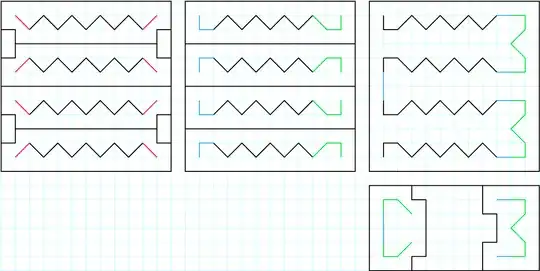

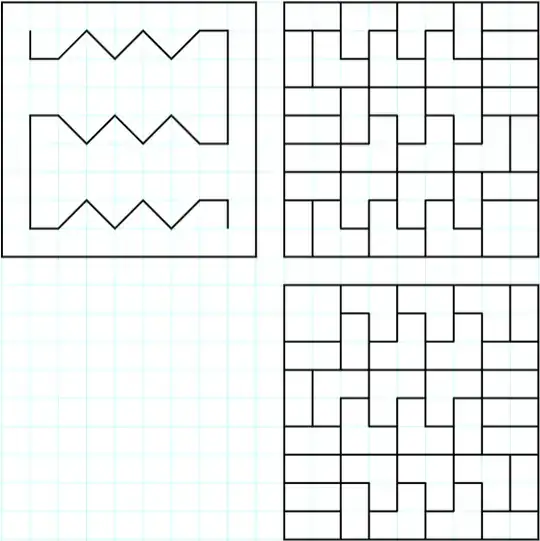

Here are ALL solutions for $n < 11$ brute-forced:

The rest of the current best solutions: $11-14$, $15-18$

The unions of all line segments of the current best solutions: $7-12$

OEIS sequence A383980

The website I use to draw the solutions: virtual-graph-paper.com, thanks to @Zoe Allen.

And a GitHub repository for anyone that wishes to optimize my C++ code or run it themselves.

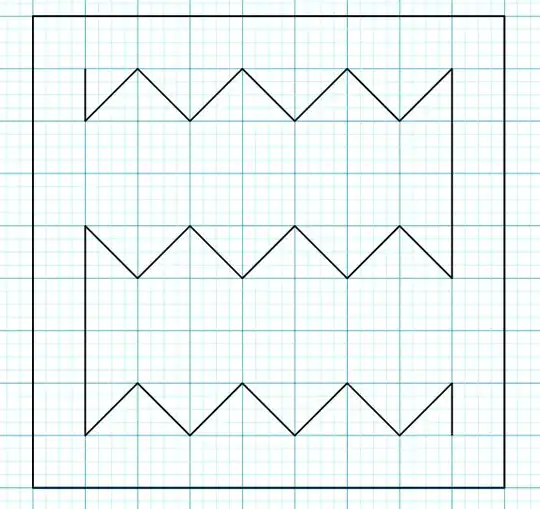

Recursive examples $(n > 4)$ and their lengths:

# of orthogonal moves: \begin{cases} O(n)&=6+O(n-3), &n>7\\ O(6)&=10\\ O(7)&=15\\ O(5)&=9 \end{cases} $$O(n)=6k+O(n-3k)=\\ =\begin{cases} 6\left(\frac{n-6}{3}\right)+10&=2n-2, &n\equiv0\mod{3}\\ 6\left(\frac{n-7}{3}\right)+15&=2n-2+3, &n\equiv1\mod{3}\\ 6\left(\frac{n-5}{3}\right)+9&=2n-2+1, &n\equiv2\mod{3}\\ \end{cases}$$

# of diagonal moves: \begin{cases} D(n)&=2n-7+D(n-3), &n>7\\ D(6)&=4\\ D(7)&=5\\ D(5)&=1 \end{cases} $$D(n)=\sum_{j=0}^{k-1}\Bigl(2\left(n-3j\right)-7\Bigr)+D(n-3k)\\ \sum_{j=0}^{k-1}\Bigl(2\left(n-3j\right)-7\Bigr)= 2nk-7k-6\sum_{j=0}^{k-1}j=\\ =(2n−7)k−6\left(\frac{k(k−1)}{2}\right)=k((2n−7)−3(k−1))\\ D(n)=k((2n−7)−3(k−1))+D(n-3k)=\\ =\begin{cases} \left(\frac{n-6}{3}\right)\left((2n-7)-3\left(\frac{n-6}{3}-1\right)\right)+4&= \frac{n(n-4)}{3}, &n\equiv0\mod{3}\\ \left(\frac{n-7}{3}\right)\left((2n-7)-3\left(\frac{n-7}{3}-1\right)\right)+5&= \frac{n(n-4)-6}{3}, &n\equiv1\mod{3}\\ \left(\frac{n-5}{3}\right)\left((2n-7)-3\left(\frac{n-5}{3}-1\right)\right)+1&= \frac{n(n-4)-2}{3}, &n\equiv2\mod{3} \end{cases}$$ Path length: $$S(n)=O(n)+\sqrt{2}D(n)$$ I suspect that there aren't any solutions better than these but I don't know how to prove that the recursion is always optimal in the limit. I have since posted what I deem to be a proof for $n\equiv0\mod{3}$ as an answer, is it correct?

I also conjecture that all cases of $n\equiv2\mod{3}$ have exactly $8$ solutions for $n>10$.

The problem could be equated to a domino tiling problem, where we want to use the smallest amount of dominos possible, this is lacking rigor for now and the constraints on them may be problematic.

Orthogonal moves only:

$n < 5$ is the same as above.

There are $n^2$ squares, the starting position can touch up to $4$ squares, every orthogonal line can touch up to $2$ new squares per unit length. From this we get $S(n)=\frac{n^2-4}{2}$. Such a path is always possible for $n\equiv0\mod{2}$, here's a recursive example:

For $n\equiv1\mod{2}$, an optimal solution's path segments are all optimal except for one, since $n^2-4\equiv1\mod{2}$, thus: $S(n)=\frac{n^2-4+1}{2}$. Here's a recursive example:

~142.07 with something close to @ZoeAllen 's method.

~142.07 with something close to @ZoeAllen 's method.