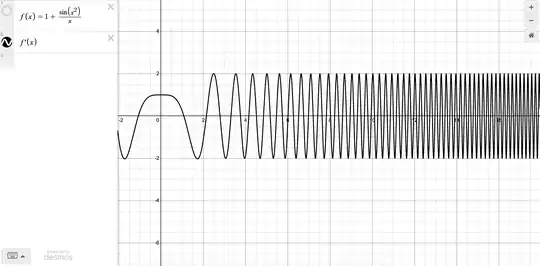

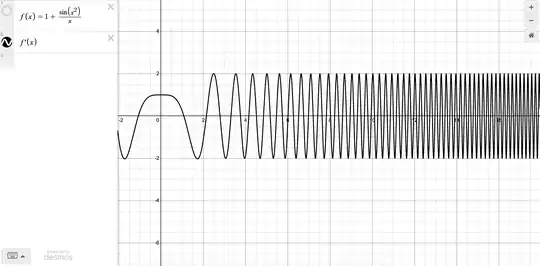

Here's an example that illustrates why differentiation does not respect asymptotics in general.

Consider the function $f(x)=1+\frac{\sin(x^2)}{x}$ defined on $(0,\infty)$. The asymptotics of this function as $x\to\infty$ are as simple as can be: $f(x)=1+O\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)$. However, we can compute

$$f'(x)=\cos(x^2)-\frac{1}{x^2}\sin(x^2)$$

which does not settle on any value as $x\to\infty$, let alone $\frac{d}{dx}1=0$. The problem is that the first term $\cos(x^2)$ oscillates indefinitely, and thus fails to have a limit:

Fundamentally, the reason the derivative behaves this way is because in $f(x)=1+\frac{\sin(x^2)}{x}$, the $x^2$ in $\sin(x^2)$ makes the sine wave oscillate faster and faster, making $\sin(x^2)$ slope steeper and steeper between $\pm 1$ as $x\to\infty$.

In general, knowing the limiting behavior of a function says nothing about how the function "approaches that limiting behavior". If you hand me a function with known asymptotics, say

\begin{align*}

g(x) &= \frac{1}{1-\frac{1}{x}}\\

&=\sum_{n=0}^\infty\frac{1}{x^n} \text{ (for $x>1$)}\\

&=1+\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{x^2}+\frac{1}{x^3}+\cdots + \frac{1}{x^n}+O\left(\frac{1}{x^{n+1}}\right)\text{ as $x\to\infty$}

\end{align*}

I can "perturb" it to get a function $\tilde g(x)$ with the same asymptotic behavior, the only difference being that it oscillates to get there. Here's an example of such a function:

$$\tilde g(x)=\left(1+\frac{\sin(e^x)}{e^x}\right)g(x)$$

Notice that $\tilde g(x)=(1+o(1))g(x)$, so $\tilde g(x)$ is a slight variation of $g(x)$; this is where the "perturbed" terminology comes from. It is easy to check that for any $n\in\mathbb N$, we have

$$\tilde g(x)=1+\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{x^2}+\frac{1}{x^3}+\cdots + \frac{1}{x^n}+O\left(\frac{1}{x^{n+1}}\right)\text{ as $x\to\infty$}$$

so $\tilde g(x)$ has the same asymptotic expansion as $g(x)$. However, the derivative $\tilde g'(x)$ fails to have a limit:

\begin{align*}

\tilde g'(x) &= \left(\cos(e^x)-e^{-x}\sin(e^x)\right)g(x)+\left(1+\frac{\sin(e^x)}{e^x}\right)g'(x)\\

&= {\color{red}{\cos(e^x)}}\underbrace{\color{red}{g(x)}}_{1+o(1)}-\underbrace{\frac{\sin(e^x)}{e^x}}_{o(1)}\underbrace{g(x)}_{1+o(1)}+\underbrace{\left(1+\frac{\sin(e^x)}{e^x}\right)}_{1+o(1)}\underbrace{g'(x)}_{o(1)}

\end{align*}

The term in red is oscillatory because $\cos(e^x)$ oscillates, but $g(x)\to 1$ as $x\to\infty$. All the other terms will go to $0$, so $\lim_{x\to\infty}\tilde g(x)$ does not exist.

Note: the reason for using $e^x$ in $\sin(e^x)/e^x$ is because when I tried to do this with the above example $\sin(x^2)/x$, some powers of $\frac{1}{x}$ would cancel when computing

$$\frac{\tilde g(x) - \sum_{n=0}^{N-1} \frac{1}{x^n}}{\frac{1}{x^N}}$$

to prove the asymptotics. This would leave some oscillatory terms $\sin(x^2)$ left over; for example, taking $\tilde g(x)=\left(1+\frac{\sin(x^2)}{x}\right)\left(1+\frac{1}{x}+\cdots\right)$, we can compute

$$\frac{\tilde g (x)-1}{\frac{1}{x}}=\frac{\frac{1+\sin(x^2)}{x}+\frac{\sin(x^2)}{x^2}+\cdots}{\frac{1}{x}}=1+{\color{red}{\sin(x^2)}}+O\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)$$

and see from the red term that $\frac{\tilde g (x)-1}{\frac{1}{x}}$ oscillates as $x\to\infty$. Changing to $e^x$ fixes this issue because $e^x$ dominates $x^N$ for every $N\in\mathbb N$.