I am invested of a simpler variation of the Littlewood conjecture, for a specific value, namely $\sqrt{2}$.

The problem

To begin, we define the function $f(x)$ for a real value $x$ as the distance from $x$ to the integer closest to it. Or written more formally:

$$f(x) = |x - \lfloor x \rceil| = |x - \text{round}(x)| = \min_{n\in Z} |x - n|$$

where $\lfloor x \rceil = \text{round}(x)$ is the round to integer "function" (Wikipedia doesn't call it a function, but functions for the process exist in language like Python, so I put that in quotes).

The problem: Calculate the following: $$\inf_{n \in \mathbb{N}, \ n \geq 1} \ (n \times f(n\sqrt{2}))$$

where the condition $n \geq 1$ is given to prevent the case $n = 0$, which just makes the product zero.

Some theoretical work

$\sqrt{2}$ has irrational measure $2$, which means that there are infinitely many pairs of integers $(p, q)$ such that

$$ 0 < \left|\sqrt{2} - \frac{p}{q}\right| < \frac{1}{q^2} $$

Define a sequence $(q_i)_{i=1}^\infty$ such that all $q_i$ has a $p_i$ that satisfy the upper equation together (that is, for each $q_i$, there exists a corresponding $p_i$ such that

$$0 < \left|\sqrt{2} - \frac{p_i}{q_i}\right| < \frac{1}{{q_i}^2}$$

and the $q_i$ are increasing. (Well, there are infinitely many of them, so just find and sort, I guess, but it doesn't really matter).

Now, let $e_i = \left|\sqrt{2} - \frac{p_i}{q_i}\right|$. As the $q_i$ gets larger, the $e_i$ tends to zero due to the squeeze theorem. At this point, let's try to substitude the number $q_i$ into the $n \times f(n \sqrt{2})$. We have:

$$ q_i \times f(q_i \sqrt{2}) = q_i \times f\left(q_i \left(\frac{p_i}{q_i} + e_i\right)\right) = q_i \times f(p_i + q_ie_i) $$

Assume that $q_i$ is extremely large, which makes $\frac{1}{q_i}$ small and $\frac{1}{{q_i}^2}$ even smaller. Since $e_i$ is bounded between $0$ and $\frac{1}{{q_i}^2}$, this would also make $e_i$ really, impossibly small. If we assume that both $e_i$ and $\frac{1}{{q_i}^2}$ are too small for them to have any meaningful difference, then we assume $e_i \approx \frac{1}{{q_i}^2}$ and we have:

$$ q_i \times f(p_i + q_ie_i) \approx q_i \times f\left(p_i + q_i \frac{1}{{q_i}^2}\right) \\ = q_i \times f\left(p_i + \frac{1}{q_i}\right) \approx q_i \times \frac{1}{q_i} = 1??? $$

(I put the question marks at the end because I'm not sure, and I felt like there are mistakes somewhere, but oh well)

But now, that is not the craziest part...

Some numerical work.

Instead of using the massive theoretical work above, I implement a piece of Python code to check over all $n \times f(n\sqrt{2})$ in a range from $1$ to some number. Here, I pick $10^7$.

def f(a: float) -> float:

return math.fabs(a - round(a))

def L(n: int) -> float:

return n * f(n * math.sqrt(2))

t = 10 ** 10 # some big value

z = 0

for i in range(1, 10 ** 7 + 1):

if L(i) <= t:

z = i

t = L(i)

print(z)

print(t)

Here, L(n) represents the value of the formula $n\times f(n\sqrt{2})$, z represents the index n where we met the smallest value of L(n), which is n * f(n * math.sqrt(2)), while t denotes the actual value itself. So here's what surprising.

print(z) prints $2$. At $z = 2, t = 0.343145\dots$.

I did not expect the value to appear so early.

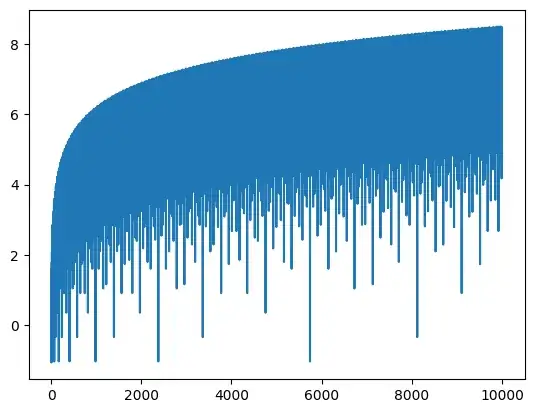

I also plotted the sequence $\log L(n)$ with $n$ from $0$ to $10^4$ as follows:

x = np.arange(1, 10001)

y = np.array([math.log(L(i)) for i in x])

y

plt.plot(x, y)

And this is the resulting image:

It's definitely interesting to see the dips, but I still can't believe the first dip appeared so early though.

What do you think?

\cdot): $a\cdot b$ or a cross (\times): $a\times b$. – CiaPan Feb 04 '25 at 10:31PythonorCfor multiplication, and I didn't remember about the $\cdot$ – ducbadatcs Feb 04 '25 at 10:33