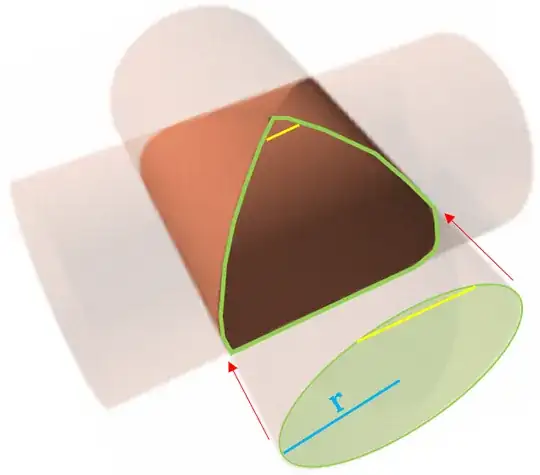

I'm wondering whether there's a way to project the circle's surface onto the corresponding part of the bicylinder's surface outlined in green (which is very similar to a spherical lune) which shows that the area increases by a ratio of 4:$\pi$ (since the area of the lune-like section of each bicylinder surface is 4$r^2$ rather than the circle's area of $\pi r^2$), like how a sphere's surface can be projected onto a cylinder to show that its surface area is 4$\pi r^2$. I don't see how the 2D version of Cavalieri's Principle would work since each corresponding yellow cross section (bicylinder:circle) would have to have a length ratio of 4:$\pi$ which isn't the case unless there's some serious visual illusion going on. Does anyone know of a way to prove this using just high-school level geometry?

Asked

Active

Viewed 45 times

0

-

2Hint: you can deduce the volume of a bicyclinder by cutting it with planes parallel to $xy$-plane. Since the area of its cross section is always $\frac{4}{\pi}$ of that for corresponding sphere. You know its volume is $\frac{4}{\pi}$ of that of a sphere. You can do the same thing to the surface area, you will find the ratio is again the same constant... – achille hui Feb 02 '25 at 14:00

-

@achille hui Thanks. What comparisons do I have to make to do the same thing for the surface area? In other words, what "cross sections" do I need to use? I didn't think that approach was working for the yellow segments. – Nate Feb 03 '25 at 00:17

-

Cut the bicyclinder and sphere by a pair of planes $z=\cos\theta \pm \epsilon$. For both solids, if you look at the normal vector for those portion of surface between these planes, you will notice they are making an angle $\theta + O(\epsilon)$ with $z$-direction. The ratio of the surface area of them equals to the ratio of perimeter of a circle and square (up to some correction of order $\epsilon$). Convince yourself these error doesn't matter as $\epsilon$ becomes smaller and smaller. – achille hui Feb 03 '25 at 05:34