Alternative approach:

The equation

$$x^4+2x^3-14x^2+2x+1=0, \tag1 $$

can be directly converted into a quadratic equation by recognizing that the equation in (1) above is a symmetric quartic equation. That is, the $~x^4~$ and $~x^0~$ coefficients are equal, and the $~x^3~$ and $~x^1~$ coefficients are equal.

Therefore, the method employed in

this answer may be used.

First, the equation in (1) above is transformed into

$$\left( ~x^2 + \frac{1}{x^2} ~\right) + 2\left( ~x + \frac{1}{x} ~\right) - 14 = 0. \tag2 $$

Then, you set $~w = \displaystyle \left( ~x + \frac{1}{x} ~\right),~$ and note that

$\displaystyle w^2 - 2 = \left( ~x^2 + \frac{1}{x^2} ~\right).$

Therefore, the equation in (2) above becomes

$$( ~w^2 - 2) + 2w - 14 = 0 \implies w^2 + 2w - 16 = 0 \implies $$

$$w = \frac{1}{2} \left[ -2 \pm \sqrt{ ~4 + 64 ~} ~\right] = -1 \pm \sqrt{17}.$$

Since $~w = \displaystyle \left( ~x + \frac{1}{x} ~\right),~$ which must be positive, the negative root above must be rejected.

Therefore,

$$w = \left( ~x + \frac{1}{x} ~\right) = -1 + \sqrt{17} \implies $$

$$x^2 + x \left( ~1 - \sqrt{17} ~\right) + 1 = 0 \implies $$

$$x = \frac{1}{2} \left[ ~\sqrt{17} - 1 \pm \sqrt{~18 - 2\sqrt{17} - 4 ~} \right]$$

$$= \frac{1}{2} \left[ ~\sqrt{17} - 1 \pm \sqrt{~14 - 2\sqrt{17} ~} \right]. \tag3 $$

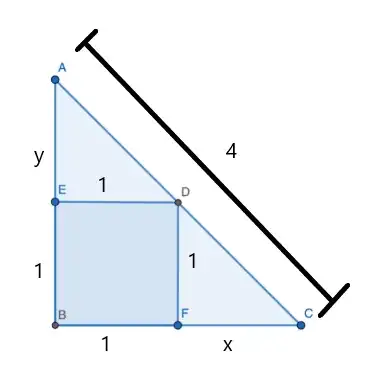

What the equation in (3) above represents is that there are $~2~$ different solutions, depending on whether $~x < y,~$ or $~y < x.$

$\underline{\text{Sanity Checking}}$

The solution given in (3) above may be routinely sanity checked to verify that both of the following constraints are satisfied:

$$\left\{ ~\frac{1}{2} \left[ ~\sqrt{17} - 1 + \sqrt{~14 - 2\sqrt{17} ~} \right] ~\right\} \\ \times \left\{ ~\frac{1}{2} \left[ ~\sqrt{17} - 1 - \sqrt{~14 - 2\sqrt{17} ~} \right] ~\right\} $$

$$= \frac{1}{4} \left\{ ~

\left[ ~18 - 2\sqrt{17} ~\right] - \left[ ~14 - 2\sqrt{17} ~\right] ~\right\} = \frac{4}{4}.$$

Note that $~(R + S)^2 + ~(R - S)^2 = 2(R^2 + S^2).$

Therefore,

$$\left\{ ~\frac{1}{2} \left[ ~\sqrt{17} + 1 + \sqrt{~14 - 2\sqrt{17} ~} \right] ~\right\}^2 \\

+ \left\{ ~\frac{1}{2} \left[ ~\sqrt{17} + 1 - \sqrt{~14 - 2\sqrt{17} ~} \right] ~\right\}^2

$$

$$= 2 \times \frac{1}{4} \times \left\{ ~\left[ ~18 + 2\sqrt{17} ~\right] + \left[ ~14 - 2\sqrt{17} ~\right] ~\right\}$$

$$= \frac{2}{4} \times (18 + 14) = 16.$$