I think this is quite a good question even if the reason $f’(0)$ is not defined is rather simple. As I’ll explain, your example does illustrate something fairly interesting.

Why $f’(0) \neq 0$:

Note that your definition of $f$ is

$$f(x) = \begin{cases}

1-x^2 & x \leq 0 \\ x^2 & x > 0

\end{cases}$$

So we have that $f(0)=1$.

Hence

$$\begin{align}

\lim_{h \to 0^+} \left( \frac{f(h) - f(0)}{h} \right) &= \lim_{h \to 0^+} \left( \frac{h^2 - 1}{h} \right) \\

&= \lim_{h \to 0^+} \left(h - \frac{1}{h}\right)

\end{align}$$

which is undefined (as $h \to 0^+$ this gets arbitrarily large.)

Your mistake is that you put $f(0)=0$ in this limit. I think your mistake is that you asserted $\lim_{h \to 0^+} f(h) = f(0)$ here, which isn’t necessarily the case, and isn’t the case for this $f$. The discontinuity of $f$ at $0$ occurs when approaching $0$ from the positive direction, hence why the this limit won’t be defined.

Your example is interesting:

But what you have observed, if I write $f(0^+)$ and $f(0^-)$ as shorthand for $\lim_{x \to 0^+} f(x)$ and $\lim_{x \to 0^-} f(x)$, that

$$\lim_{h \to 0^+} \left( \frac{f(h) - f(0^+)}{h} \right) = \lim_{h \to 0^-} \left( \frac{f(h) - f(0^-)}{h} \right) $$

Or alternatively, that $$\lim_{x \to 0^+} f’(x) = \lim_{x \to 0^{-}} f’(x).$$

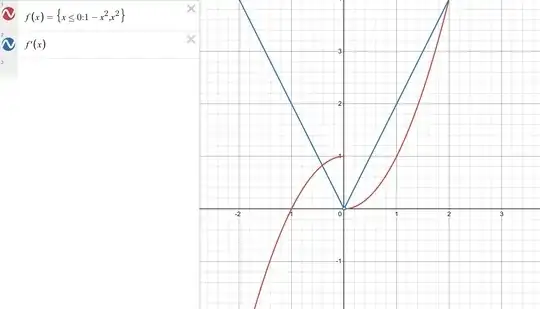

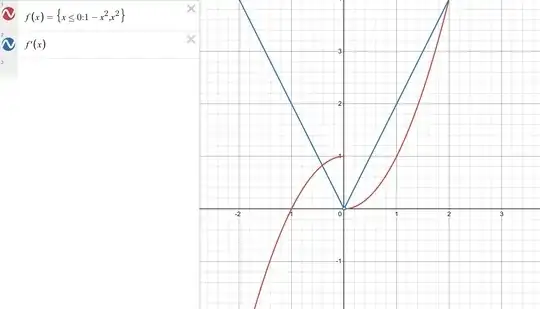

What this means is that, while $f$ is discontinuous at $x=0$ and cannot be extended to a continuous function. However, $f’$ is discontinuous (in particular undefined at a point) but it can be extended to a continuous function. Formally, what I mean is that there does not exist a continuous function $g$ such that $g(x) = f(x)$ for $x \neq 0$, but there does exist a function $g$ such that $g(x) = f’(x)$ for $x \neq 0$ (namely, $g(0)=0$). Perhaps the easiest way to see this is from the graphs of $f$ and $f’$:

(Image courtesy of Desmos, modified by me to emphasise the discontinuity)

To help emphasise this further, you might want to consider what the anti-derivative of a function which is continuous at all but a a few isolated points can look. Can you see how different intervals of the antiderivative could have different constants of integration, yet still be valid anti-derivatives? How does this relate back to our example?