I'm asking these three questions because I'm still missing a point in the proof of the fact that the solid pyramid $P$ in $\mathbb{R}^3$ is not a manifold with corner, as the top vertex is not a corner.

So to define what a manifold with corner is, I'm using this paper, where the definition is in Section 2, but I'm including the gist in my post.

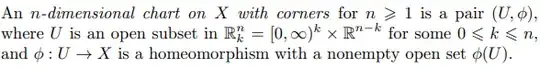

Definition of a manifold with corners:

Let $X$ be a a paracompact Hausdorff topological space. Then,

Two charts $(U,\phi), (V, \psi)$ are compatible if their transition map $\psi^{-1}\circ \phi: \phi^{-1}(\phi(U)\cap \psi(V)) \to \psi^{-1}(\phi(U)\cap \psi(V)$ is smooth.

An $n$-dimensional smooth atlas on $X$ is a family or collection of $\{U_i, \phi_i\}_{i\in \mathcal{I}}$ with smooth transition maps so that $\bigcup_{i\in I}\phi(U_i)=X.$

Finally, a manifold with corner $X$ is a paracompact, Hausdorff, topological space, equipped with a maximal $n$-dimensional smooth atlas.

Consider the above definition.

Question 1: How could we use the above definition to show that the top vertex of the pyramid P is not a corner, i.e. $P$ is not a manifold with corner? In this regard, I saw this answer on MSE which proves that top vertex is not a corner by the following arguments:

- a linear isomorphism (bijective linear map) of $\mathbb{R}^3$ preserves the number of edges of a cone.

- if there was a local diffeomorphism between an open neighborhood of the top vertex of $P$ to an open neighborhood of the origin in $[0,\infty)^k \times \mathbb{R}^{3-k}, 0 \le k \le 3,$ then its derivative at the top vertex would take the tangent cone of $P$ at the top vertex to the tangent cone at the origin in $[0,\infty)^k \times \mathbb{R}^{3-k}, 0 \le k \le 3,$ which is itself. So it'd take a cone with $4$ edges to a cone with $k$-edges, $0\le k \le 3.$

- By the first argument, the above is impossible, since the above derivative is a linear isomorpshism.

I understand the argument above. What I don't understand is that why the above implies that I cannot have two local charts $\{(U,\phi), (V, \psi)\}$ around the top vertex of $P$ so that the transition map $\psi^{-1}\circ \phi: \phi^{-1}(\phi(U)\cap \psi(V)) \to \psi^{-1}(\phi(U)\cap \psi(V)$ is smooth? Why not take $U=V, \phi=\psi,$ so the transition map is the identity map on $\mathbb{R}^3,$ much like the same way we show that the graph $G$ of $x\mapsto |x|$ is a smooth manifold, as near the origin, one can take canonical projection $\mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{R}^1$ on the graph $G$ near $0$ as the chart maps which is a homeomorphism, and the transition map of two such chart maps is the identity map on $\mathbb{R}^1,$ implying that $G$ is a smooth manifold. Of course, it's not a smooth submanifold of $\mathbb{R}^2!$

Question 2: What are some examples of topological manifolds $X$ in $\mathbb{R}^3$ that are not smooth manifolds, or smooth manifolds with boundaries or corners, according to the above definition? So in essence, we need to show that there cannot exist smooth atlases on $X$ near a certain $x\in X.$

Question 3: Is there any definition of a manifold with corners that'll make the pyramid $P$ or other such objects with many edges coming out of a point (sorry if this is vague, but I hope that the point is still clear) a manifold with corner?