problem: How many triangles can be formed by the points of a regular $25$-gon so that triangles do not share any side with that $25$-gon? Triangles are considered the same if they differ only by a rotation of the $25$-gon.

My approach:

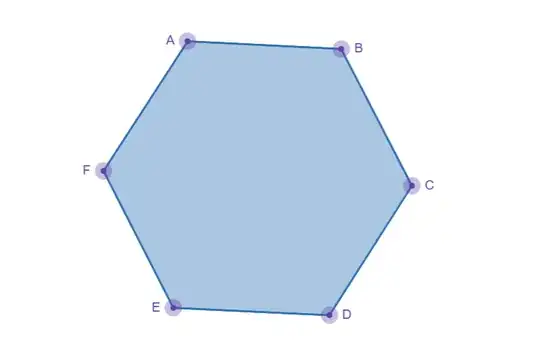

Let's consider a regular $6$ gon. Since, this a regular $6$ gon, it doesn't matter where we put the $1$st point. All will be equivalent. Let's say, our $1$st point is $A$. So, we can't put the $2$nd point in $B$ and $F$ otherwise, $AB$ and $AF$ will be a side of that polygon. We have $6-1-2=3$ choices.

$1$st case: We will not take common. Let's say, we will put the $2$nd point in $C$ or $E$. The points, we can't put the $3$rd point are $B$,$D$,$F$,$D$. $B$ is common by $A$ and $F$ is common by $A$. Now we don't want that. We will have $2$ common so $2$ points. So, $3-2=1$. Let's put $2$nd point. We have $1$ choice which is $D$. How many choices are left for the $3$rd point? $1-1=0$. Oh, no choices. So, no triangle.

$2$nd case: We will take common. Even though , we have $6-3=3$ choices, since $A$ have $2$ commons, if we want to have common, we have $2$ choices to put the $2$nd point. Let's say, we will put $2$nd point on $C$. $B$ is common. We have $6-1$($A$ point it self)-$2$($F$ and $B$)-$1$($C$ itself)-$1$($D$)=$1$. And that point is $E$.

Let's do it for $25$ gon. we will not take common first. We have $25-1-2=22$ choices for the $2$nd point. Since, we don't want common, we have $22-2=20$ choices. We have $1$ point $A$ others are the neighbor points($2$). Also, we have the $2$nd point.$2$nd point has 2 neighbors too. We have $25-1-2-1-2=19$ ways we can put the $3$rd point. The amount of triangles are $20*19=380$. If we have common, we have $2$ choices for the $2$nd point. We will choose one. Since, we have common, we have $25-1-2-1-1=20$ choices for the $3$rd point. The amount of triangle are $20*2=40$. In total, the amount of triangle are $380+40=420$.

Conclusion: This is quite tricky that's why I recommend to understand every line. I posted here to make sure that my solution is correct or not. Please, help me.