Let $M$ be a simply-connected non-contractible 4-manifold without boundary. Note that I am not assuming $M$ is closed.

Can it be the case that $M$ is a $K(G, n)$ for some abelian group $G$ and $n > 0$?

I suspect the answer is "no," but haven't been able to close out the case that $M$ is open. Here's what I've been able to come up with: First, note that the answer is "no" when $M$ is closed: Using Poincaré Duality, we immediately find that $H_1(M) = H^1(M) = H_3(M) = H^3(M) = 0$. If $H_2(M) = 0$ as well, then $M$ is a simply-connected integral homology sphere, thus homotopy equivalent to $S^4$ which is not an Eilenberg-Mac Lane space. Otherwise $H_2(M)$ must be finitely generated and torsion free (the torsion would appear as a summand of $H^3(M)$ which is trivial), so $H_2(M) \cong \mathbb{Z}^d$ for some $d > 0$. The only chance for $M$ to be an Eilenberg-Mac Lane space is thus if it is a $K(\mathbb{Z}^d, 2)$, but we know a model of this homotopy type, namely $(\mathbb{C}\mathrm{P}^\infty)^d$, which has non-trivial homology in infinitely many degrees, ruling out this possibility as well.

If $M$ is open, it can only be a $K(G, 2)$ or a $K(G, 3)$. In fact, it can only be a $K(G, 2)$: Any open 4-manifold has the homotopy type of a 3-dimensional CW-complex, so if it were a $K(G, 3)$ the group $G$ would have to be free of at most countable rank, and this is ruled out by the fact that $K(\mathbb{Z}, 3)$ has non-trivial homology in infinitely many degrees. The only thing I find myself able to say about the $K(G, 2)$-case is that $G$ cannot be finitely generated, for similar reasons. I haven't been able to rule out the case that $G$ is a non-finitely generated countable group, and don't feel like I have the necessary knowledge to do so (if my hunch that the statement is false is in fact correct). I know very little about 4-manifolds and definitely ought to brush up my knowledge of the theory of Eilenberg-Mac Lane spaces and their co/homology.

With these observations, my question thus becomes: Is there an open 4-manifold $M$ and a non-finitely generated countable group $G$ such that $M$ is a $K(G, 2)$?

Edit: I've managed to show that $G$ must be divisible. Indeed, note that $M$ must be a $M(G, 2)$ since $H_3(M)$ vanishes by Hurewicz and $H_k(M)$ vanishes for $k \geq 4$ since it is an open 4-manifold. Let $p \in \mathbb{N}$ be a prime number and consider the short exact sequence

$$

0 \to G \xrightarrow{\cdot p} G \to \underbrace{\operatorname{coker} (\cdot p)}_{=: G'} \to 0

$$

Applying $K({{-}}, 2)$ yields a fibre sequence

$$

K(G, 2) \to K(G, 2) \to K(G', 2)

$$

giving in turn rise to a Serre spectral sequence

$$

E^2_{p, q} = H_p(K(G', 2); H_q(K(G, 2))) \implies H_{p + q}(K(G, 2))

$$

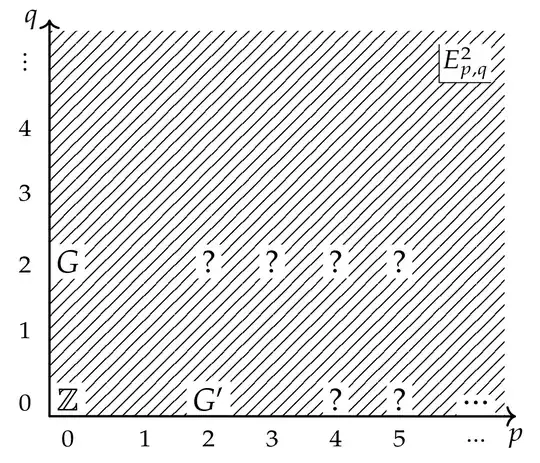

whose $E^2$-page looks like this:

(here everything shaded in is zero). Note that the group $E^2_{4, 0} = H_4(K(G', 2))$ is not affected by any differentials and survives to the $E^\infty$-page where it contributes to the convergence to $H_4(K(G, 2)) = 0$, so it suffices to show that this group is non-zero if $G'$ is for a contradiction. But note that $G'$ is an $\mathbb{F}_p$-vector space, so in fact it suffices to show that $H_4(K(\mathbb{Z} / p, 2)) \neq 0$, and this is easy: Simply note that

$$

H^4(K(\mathbb{Z} / p, 2); \mathbb{Z} / p) \cong [K(\mathbb{Z} / p, 2), K(\mathbb{Z} / p, 4)] \neq 0

$$

since this latter set is in bijection with cohomology operations $H^2({{-}}; \mathbb{Z} / p) \Rightarrow H^4({{-}}; \mathbb{Z} / p)$ and the cup-square is one such operation, so since $H_3(K(\mathbb{Z} / p, 2)) = 0$ by Hurewicz the UCT implies that $H_4(K(\mathbb{Z} / p, 2)) \neq 0$. Letting $p$ range over all possible primes, we thus obtain that $G$ is divisible.

(here everything shaded in is zero). Note that the group $E^2_{4, 0} = H_4(K(G', 2))$ is not affected by any differentials and survives to the $E^\infty$-page where it contributes to the convergence to $H_4(K(G, 2)) = 0$, so it suffices to show that this group is non-zero if $G'$ is for a contradiction. But note that $G'$ is an $\mathbb{F}_p$-vector space, so in fact it suffices to show that $H_4(K(\mathbb{Z} / p, 2)) \neq 0$, and this is easy: Simply note that

$$

H^4(K(\mathbb{Z} / p, 2); \mathbb{Z} / p) \cong [K(\mathbb{Z} / p, 2), K(\mathbb{Z} / p, 4)] \neq 0

$$

since this latter set is in bijection with cohomology operations $H^2({{-}}; \mathbb{Z} / p) \Rightarrow H^4({{-}}; \mathbb{Z} / p)$ and the cup-square is one such operation, so since $H_3(K(\mathbb{Z} / p, 2)) = 0$ by Hurewicz the UCT implies that $H_4(K(\mathbb{Z} / p, 2)) \neq 0$. Letting $p$ range over all possible primes, we thus obtain that $G$ is divisible.

This implies that $G$ is a direct sum of copies of $\mathbb{Q}$ and of $\mathbb{Z}_{p^\infty}$ for prime $p$. In fact there are no summands of the first kind since $H^*(K(\mathbb{Q}, 2)) \cong \mathbb{Q}[\iota_2]$ is infinite-dimensional (see also this answer kindly linked by Moishe Kohan in the comments below). We can also rule out that there are copies of $\mathbb{Z}_{2^\infty}$, either by another spectral sequence argument analogous to the one above (consider $K(H, 2) \to K(G, 2) \to K(G, 2)$ where $H := \ker(G \xrightarrow{\cdot 2} G)$ and use that $H_4(K(\mathbb{Z} / 2, 2)) \cong \mathbb{Z} / 4$), or by virtue of this answer.

I have not been able to progress further. By the last answer I linked this answer is consistent at face value with the usual constraints being a manifold imposes on the co/homology (I have thought about Poincaré duality but found myself unable to say anything about $H^*_c(M)$ beyond what's implied by the duality theorem) and homotopy groups of $M$, and it seems unlikely that the tools I've used so far will carry me any further (unless there's a result on minimal cell structures of $K(\mathbb{Z}_{p^\infty}, 2)$s out there, but this strikes me as unlikely: These usually make use of co/homological dimension).

As I have stated above, I know very little about 4-manifolds, so I'm hoping that perhaps something can be said from that angle.

Summing up, the question thus reduces to: Is there an open 4-manifold $M$ which is a $K(G, 2)$ where $G$ is an at most countable sum of Prüfer groups $\mathbb{Z}_{p^\infty}$ for primes $p \neq 2$?

Of course answers using different routes of attack are also very welcome!