I am quite confused as to the following theorem and proof from Evan's PDE

where $$\Phi(x) = \begin{cases} - \frac{1}{2 \pi} \log |x| & \text{if $n= 2$} \\ \frac{1}{n(n-2)\alpha (n)} \frac{1}{|x|^{n-2}} &\text{if $n \geq 3$} \end{cases},$$

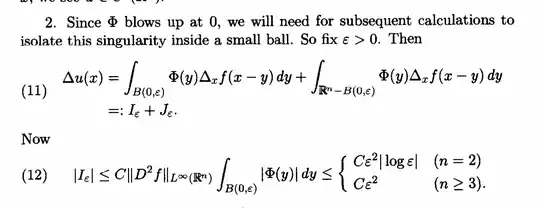

My issue with the proof is that I do not see how you can't justify $u$ being twice differentiable. I found a stackexchange post asking this very same question

theorem 1 chapter 2 - Evans PDE

Some of the people asking the post said that $\Phi$ is locally integrable, however, I do not agree. When $n=3$, along any ball centered about the origin we do not have integrability. Someone seemed to have a similar concern as mine in this post:evans book pde estimate question, however, the accepted answer seems to suggest that we "just" need to use polar coordinates. The theorem they quote in the appendix of Evans book seems to require continuity, and this is is not present here.

Could someone help me understand what is going on here?

Question: I do not see how what is given proves that $u$ is twice differentiable. The author claims it is by uniform continuity, then there is a stack exchange post elaborating on it. The logic of the post seems faulty since Φ is not locally integrable when =3 . My question is, am I right in thinking that Φ is not locally integrable, and if so, how does one approach proving the theorem then?