A final answer, which shows that in fact the majority of linear systems are consistent.

In everything that follows, we're working over $\mathbb F_2$, the field with 2 elements.

Following Joriki, we define $j(n)$ to the be probability that an $n \times n$

random matrix over $F_2$ has full rank, i.e., rank $n$, i.e., $n$ independent

columns. Let's look at $n = 4$, i.e., a $ 4 \times 4$ matrix of zero 0s and 1s.

The first column will be dependent $1$ times (when it's all zeros), hence

independent $2^4 - 1 = 15$ times,

so the probability that it's independent is

$$ \frac{15}{16}.$$

The second vector will be independent of the first if it's not in the span of

the first, which has 2 items, i.e., $\frac{14}{16} = \frac{7}{8}$ of the time,

so the probability that the first two are independent is

$$

\frac{15}{16}\cdot\frac{7}{8}.

$$

The third will be independent of the first two if it's not in their span, which has four elements,

i.e., $\frac{12}{16} = \frac{3}{4}$ of the time, and the fourth will be independent

of the first three $\frac{1}{2}$ of the time. So

$$

j(4) = 1 \cdot \frac{15}{16}\cdot\frac{7}{8}\cdot\frac{3}{4}\cdot\frac{1}{2}

$$

where I've thrown in a factor of $1$ at the front, and I'll call that $j(0)$. You

can easily see that in general

$$

j(n) = \frac{2^n - 1}{2^n} j(n-1) \tag{1}.

$$

We can generalize to give our partial computations names. We'll define $J(n, k)$

(for $n \le k)$ to

be the probability that an $n \times k$ matrix has rank $k$, and from the pattern

above, infer that

$$

J(n, k) = \frac{2^{n+1-k} - 1}{2^{n+1-k}} \cdot J(n, k-1).

$$

In particular, note that

$$

J(n, n) = \frac{1}{2} J(n,n-1)

$$

and

$$

J(n, n) = \frac{3}{4}\cdot \frac{1}{2} J(n, n-2)

$$

or, inverting things,

$$

J(n, n-1) = 2 J(n,n) \\ \tag{j1}

$$

and that

$$J(n, n-2) = \frac{8}{3} J(n, n) \tag{j2}

$$

Now (for $r \le k$) define $F(n, k, r)$ to be the fraction of all $n \times k$ matrices that have rank $r$ (and define it to be zero for $r > k$). As in the previous answer discussing the number of such matrices, there's a recurrence for $F$ namely

$$

F(n, k, r) = \begin{cases}

2^{-nk} & r = 0 \\

0& k = 0, r > 0 \\

0 & r > k \\

(1 - 2^{-(n-r+1)}) F(n, k-1, r-1) + 2^{-(n-r)} F(n, k-1, r) & \text{otherwise}

\end{cases} \tag{f1}

$$

We can compute an explicit table of $F(n, k, r)$-values for $n = 5$, for example:

1.0000 0 0 0 0 0

0.0312 0.9688 0 0 0 0

0.0010 0.0908 0.9082 0 0 0

0.0000 0.0066 0.1987 0.7947 0 0

0.0000 0.0004 0.0310 0.3725 0.5960 0

0.0000 0.0000 0.0043 0.1203 0.5774 0.2980

where the row index is the number $k$ of columns, and the column index is the rank $r$, and both run from $0$ to $5$. We see that a $5 \times 5$ matrix has about a 30% change of being invertible.

The entries along the diagonal are just $j(0), j(1), \ldots, j(5)$, as you can see by comparing the definitions of $j$ and $F$.

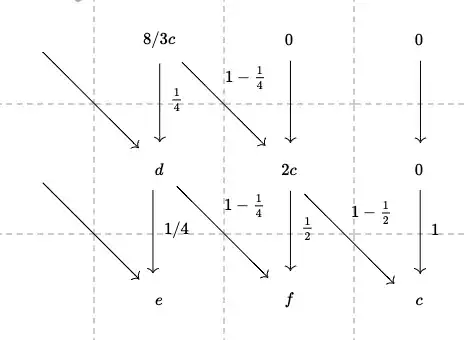

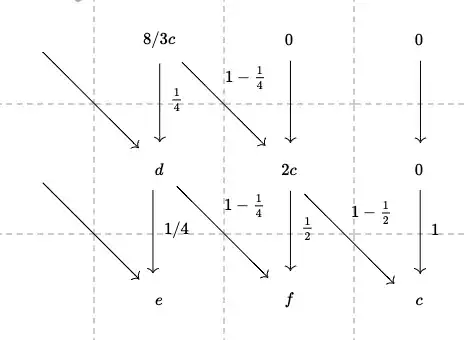

You can see that the next-to-last diagonal entry, 0.5960 is about twice the last one, 0.2960, and that's no coincidence: it follows from equation j1; similarly, the $0.7947$ is $\frac{8}{3}$ of 0.2960, which follows from equation j2. If we replace that bottom-right entry with "c", we now have

(8/3)c 0 0

0.3725 2c 0

0.1203 0.5774 c

Note to the reader: I focused on this 3 by 3 block of the table after lots of simulations and experiments on the computer showed me that most of the consistent systems, for any $n > 3$ were represented by data in this block. For those with $n \le 3$, we can check the claim by hand. Now, back to the exposition.

The recurrence for $F$, in Equation f1, show that each value in this table can be computed as a linear combination of the one above, and the one above-and-to-the-left. Here's that same statement, with the coefficients filled in from Equation f1, but with the numerical values replaced by symbols so that we're not stuck on the $n = 5$ case:

(Diagram source here.)

Now we can estimate $d, e,$ and $f$ as follows. First, $d$ is a sum of $2c/3$ and something else, so we have $d > \dfrac{2c}{3}$. Similarly, $e$ is at least $\dfrac{1}{4}$ of $d$, so $e > \dfrac{c}{6}$. And finally,

\begin{align}

f

&= \frac{1}{2} 2c + (1 - \frac{1}{4}) d \\

&> c + \frac{3}{4} \frac{2c}{3} \\

&> c + \frac{c}{2} = \frac{3}{2}c

\end{align}

So the last three entries in the last line of that table are at least

$$

\pmatrix{\frac{c}{6} & \frac{3}{2}c & c }.

$$

In other words, $c$ of the matrices have full rank, at least $3c/2$ have rank $n-1$ and at least $\dfrac{c}{6}$ have rank $n-2$.

Now let's look not just at matrices, but at systems of equations, i.e., pairs $(A, b)$ where $A$ is an $n \times n$ matrix and $b$ is an $n$-vector, and the system they represent is

$$

Ax = b.

$$

This system is consistent (i.e., has a solution) exactly if $b$ is in the column space of $A$, so if $A$ is full-rank, then any system $(A, b)$ is consistent. If $A$ has rank $n-1$, then the column space of $A$ is exactly half of the $2^n$ items in $\mathbb F^n$, so there are $2^{n-1}$ vectors $b$ with $(A, b)$ being consistent. And if $A$ has rank $n-2$, then only a quarter of all target vectors lie in its column spaces, so there are $2^{n-2}$ systems $(A, b)$ that are consistent.

Summing these facts up, the last three entries in our table correspond to a total of

$$

2^{n-2} 2^{n^2}e + 2^{n-1} 2^{n^2} f + 2^n 2^{n^2}c

$$

consistent systems. As a fraction of the $2^n \cdot 2^{n^2}$ systems overall, we find that the consistent systems constitute at least a fraction

$$

\begin{align}

K

&= \frac{2^{n-2} e + 2^{n-1} f + 2^n c}{2^n} \\

&= e/4 + f/2 + c \\

&> \frac{c}{24} + \frac{3c}{4} + c \\

&= \frac{43c}{24} \\

\end{align}

$$

Fortunately, it's easy to see that $j$ is a decreasing function of $n$, and given that its limit as $n \to \infty$ is slightly more than $28.8$, we can estimate to see that

$$

K = \frac{43}{24} c > \frac{43}{24} \cdot 28 = 50 ~ \frac{1}{6},

$$

so in fact more than half of all linear systems over $\mathbb F_2$ are in fact consistent!