This is quite a long answer...as you already got a great answer. You might peek at it for some real reason why you should adopt that method of periods.

The main problem arises in the range of the arcsine.

First, let's do it the simple trigonometric identity way:

$$I=\int_0^\pi \sqrt{1-\sin 2x}\text dx=\int_0^\pi \sqrt{\sin^2x+\cos^2x-2\sin x\cos x}\text dx=\int_0^\pi \sqrt{(\cos x-\sin x)^2}\text dx=\int_0^\pi |\cos x-\sin x| \text dx$$

Now, for $x\in [0,\pi]$, $(\cos x-\sin x)$ would take positive values (including zero) in the interval $[0,\frac{\pi}{4}]$ and negative values in $(\frac{\pi}{4},\pi]$.

So, we have to split the integral for this two intervals as the mod function would be negative in the second interval. Then,

$$\int_0^\pi |\cos x-\sin x|\text dx=\int_0^{\pi/4} (\cos x-\sin x)\text dx+\int_{\pi/4}^\pi -(\cos x-\sin x)\text dx$$

Which would give:

$$I=[\sin x+\cos x]_0^{\pi/4}-[\sin x+\cos x]_{\pi/4}^\pi=2\sqrt2.$$

So, we have got our answer now, let's begin with the substitution method.

We let:

$$t=1-\sin 2x$$

Since, $x\in [0,\pi]$ so $t\in[0,2]$.

Now,

$$t=1-\sin 2x \implies x=\frac{1}{2}\arcsin (1-t)\tag{1}$$

Here's the catch: The range of $x$ as implied by the above relation is $[-\frac{\pi}{4},\frac{\pi}{4}]$ but in the integral the original limit requires it to be $[0,\pi]$.

Why this happened?

See, the "principle" range of arcsine is $[\frac{-\pi}{2},\frac{\pi}{2}]$. So, from $eq(1)$, we get that:

$$\frac{-\pi}{2}≤2x≤\frac{\pi}{2} \implies \frac{-\pi}{4}≤x≤\frac{\pi}{4} \tag{2}$$

Then, so as to cover the whole range of $x$ i.e. $[0,\pi]$, we have to choose the range of arcsine ourselves and split the integral into the corresponding intervals of range of $x$ which comes form each of the part. Let's decode it:

We have to choose those ranges of arcsine which makes it a function as well as help us extend our range of $x$.

For example, consider the range $[\frac{\pi}{2},\frac{3\pi}{2}]$.We can cover the domain $(-1,1)$ using this range as the sine takes all the values from $1$ to $-1$ exactly one time in this interval.This shows that it makes the arcsine a function.

Now, consider the $eq(1)$ with this range. Then, $x$ would follow:

$$\frac{\pi}{2}≤2x≤\frac{3\pi}{2}\implies \frac{\pi}{4}≤x≤\frac{3\pi}{4}\tag{3}$$

Clearly, we have extended the range of $x$ till $3\pi/4$. But we are still less than $\pi$.

Consider another range of arcsine to be $[\frac{3\pi}{2},\frac{5\pi}{2}]$.This again ensures that arsine if a function as before.

Now, the range of $x$ for this range of arcsine would be:

$$\frac{3\pi}{4}≤x≤\frac{5\pi}{4}\tag{4}$$

So, we have covered the whole range which we needed for $x$ (actually beyond it).

Now, let's turn to the calculations:

$$

x=\frac{1}{2}\arcsin(1-t)\implies \frac{\text dx}{\text dt} =

\begin{cases}

\frac{-1}{2\sqrt{2t-t^2}} &\quad\text{if}\quad x\in [0,\frac{\pi}{4}]\cup[\frac{3\pi}{4},\frac{5\pi}{4}]\\

\frac{1}{2\sqrt{2t-t^2}} &\quad\text{if}\quad x\in [\frac{\pi}{4},\frac{3\pi}{4}] \\

\end{cases}\tag{5}

$$

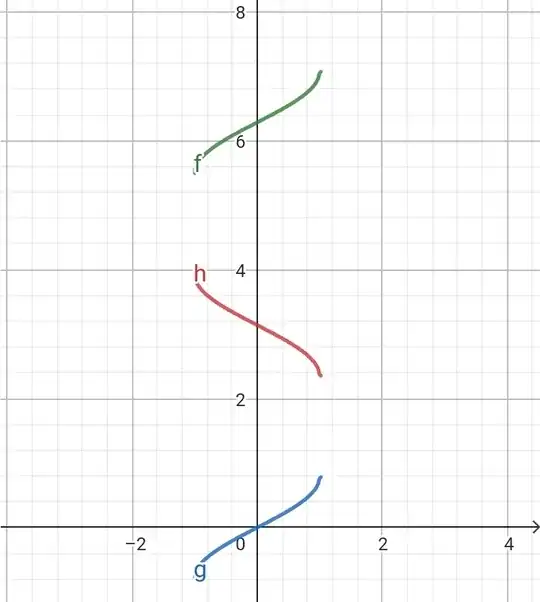

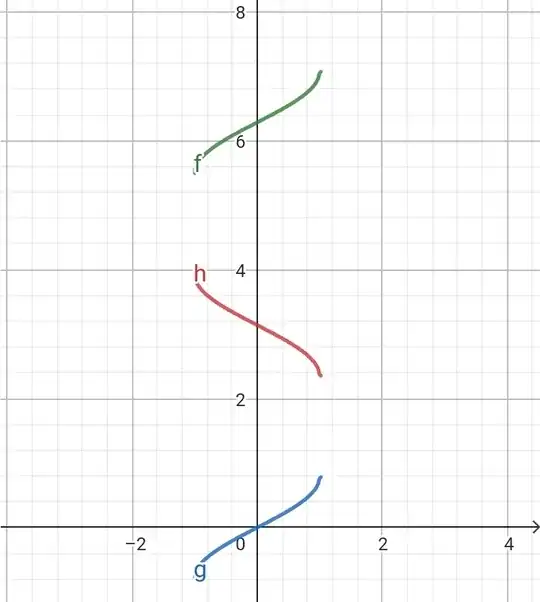

This is because:[Graphs of arcsine with ranges $[\frac{3\pi}{2},\frac{5\pi}{2}]$(top), $[\frac{\pi}{2},\frac{3\pi}{2}]$(middle) and $[\frac{-\pi}{2},\frac{\pi}{2}]$(bottom)]

Clearly, the slope of the middle one in negative of other two hence expressed as derivative in $eq(5).$

Now, the splitting:

$$I=\int_0^\pi \sqrt{1-\sin 2x}\text dx=\int_0^{\pi/4} \sqrt{1-\sin 2x}\text dx+\int_{\pi/4}^{3\pi/4} \sqrt{1-\sin 2x}\text dx+\int_{3\pi/4}^\pi \sqrt{1-\sin 2x}\text dx$$

By substitution and using $eq(5)$, we get:

$$I=\int_1^0-\frac{\sqrt t}{2\sqrt{2t-t^2}}\text dt+\int_0^2\frac{\sqrt t}{2\sqrt{2t-t^2}}\text dt+\int_2^1(-)\frac{\sqrt t}{2\sqrt{2t-t^2}}\text dt=[\sqrt{2-t}]_1^0+[\sqrt{2-t}]_2^0+[\sqrt{2-t}]_2^1=2\sqrt2.$$

The limits of $t$ are set accordingly as the interval of $x$ using the $eq(1)$.