I think that you didn't read carefully enough. Lewis Carroll is actually solving a different problem -- the probability that a random triangle is acute, not the probability that a random triangle whose vertices lie on a particular circle is acute.

You might want to consider the following apparent conundrum: if you pick 3 points in the plane, there's always a circle passing through them (unless they're collinear, which is a probability-zero event). So if we were considering that circle in the problem you stated, the probability that the triangle would be acute would be $\frac34$. But what Carroll observed was that this probability was zero. What's going on???

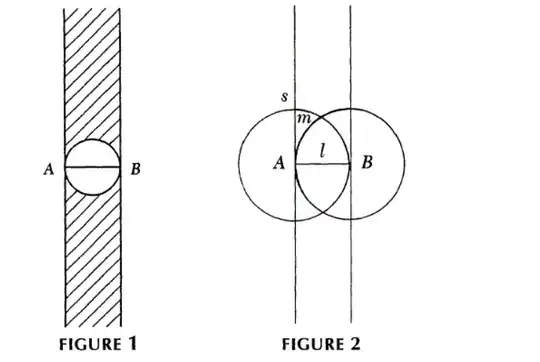

BTW, Carroll's logic is a little suspect: he says that the great preponderance of points is outside the narrow shaded strip in Figure 1. But is the great preponderance of chosen points outside that strip? You might argue that by some sort of "equal areas give equal probabilities" argument it clearly is. Unfortunately, there's no probability distribution on the plane that gives equal probabilities to equal areas (and indeed, there's nothing corresponding to it on the real line, either). So Carroll's argument, although clever, misses out on a subtely.