The following should work : it gives uniqueness in all cases, and existence under a simple condition. The unique solution often has a constant plateau as highlighted in my previous answer.

Statement

Let $a,k > 0$ and $y_a \in [0,k]$, and denote by $(P)$ the boundary value problem

$$

(1 + y'^2) y = k, \quad y(0) = 0,\quad y(a) = y_a.

$$

Let $\mathcal{B}_k$ be the brachistrochrone curve defined parametrically by

$$

\mathcal{B}_k(x(t)) = y(t) \quad \text{where} \quad \left\{\begin{array}{rcl} x(t) &=& \frac{k}{2} \left(t - \sin(t)\right)\\

y(t)&=& \frac{k}{2} \left(1 - \cos(t)\right)\end{array} \right.

$$

This curve satisfies the differential equation

$$

(1 + \mathcal{B}_k'^2)\mathcal{B}_k = k

$$

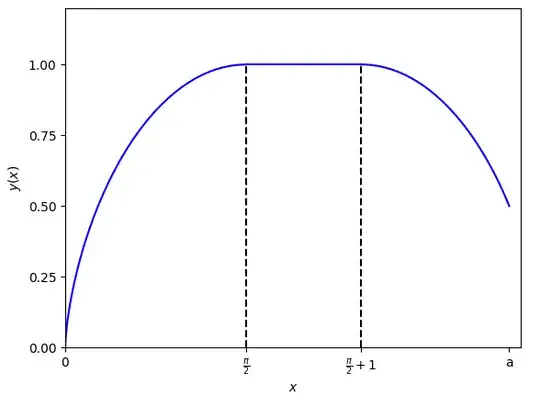

and $\mathcal{B}_k(0) = 0$. Let $s_0 := x(\pi) = \frac{k\pi}{2}$. Then

A) If $a \geq s_0$, there exists a unique solution to the problem $(P)$. This solution agrees with $\mathcal{B}_k$ on $[0,s_0]$. Moreover, there is $s_\infty \in (s_0,a]$ such that $y$ agrees with $x\mapsto \mathcal{B}_k(x + s_0 - s_\infty)$ on $[s_\infty,a]$ and $y$ is constant equal to $k$ on $[s_0,s_\infty]$.

B) If $a < s_0$, then a solution exists if and only if $y_a = \mathcal{B}_k(a)$, and in this case it is $\mathcal{B}_k$.

Remark The value of $s_\infty$ is given by $s_\infty = a - (s_0 - s^*)$, where $s^* \in [0,s_0]$ is the unique solution of

$$\mathcal{B}_k(s^*) = y_a.$$

Proof :

The proof involves the following steps:

- Prove that for every solution $y$, there is $\varepsilon > 0$ such that $y$ agrees with $\mathcal{B}_k$ on $[0,\varepsilon]$. This is the trickiest part (or at least, I did not find anything smarter).

- Deduce via the Cauchy-Lipschitz theorem that all solutions coincide with $\mathcal{B}_k$ on $[0,\min(s_0,a)]$. If $a < s_0$, this gives statement B, and otherwise, we deduce that $y'(s_0) = 0$.

- Show that there exists $s_\infty \in (s_0,a]$ such that all solutions to $(P)$ agree on $[s_\infty,a]$ and satisfy $y'(s_\infty) = 0$.

- Using the Lemma in my previous answer, conclude that all solutions are constant equal to $k$ on the interval $[s_0,s_\infty]$.

$\bullet$ Step 1

We can use the physicist's trick which is nicely described at the bottom of this wikipedia page (in french, but I'll expand on it here) https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Courbe_brachistochrone

First, observe that by continuity of $y$, there is $\varepsilon \in (0,a)$ such that $0 < y(x) \leq \frac{k}{2}$ for all $x \in (0,\varepsilon]$. This implies that $y'(x) \neq 0$ on $(0,\varepsilon]$, so it keeps a constant on this interval by continuity. So we have

$$y'(x) = \sigma \sqrt{\frac{k - y}{y}}\quad \forall x \in (0,\varepsilon]$$

where $\sigma$ is either $1$ or $-1$. But $\sigma$ must of course be $1$, and this can be seen, e.g., by writing

$$y'(x) y(x) = \sigma \sqrt{y(k-y)} \implies \frac{y^2(\varepsilon)}{2} = \sigma \int_{0}^{\varepsilon} \sqrt{y(x)(k-y(x))}dx\,.$$

Now that we have settled that

$$y'(x) = \sqrt{\frac{k-y(x)}{y(x)}} \quad \forall x \in (0,\varepsilon],$$

we deduce that $y$ is strictly increasing on $[0,\varepsilon]$, and there exists a continuous, strictly increasing function $\theta:[0,\varepsilon] \to \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0}$ such that $y(x) = k\sin^2(\theta(x)/2)$. We deduce from the differential equation that $y' = \cot \frac{\theta}{2}$, and also by differentiating directly, that $y' = k\sin(\theta/2) \cos(\theta/2) \theta'$. Equating these two expressions of $y'$, we find that $\theta$ satisfies

$$\theta'(x) = \frac{1}{k \sin^2 \frac{\theta(x)}{2}}, \quad \forall x \in (0,\varepsilon]$$

with $\theta(0) = 0$.

The next part of this trick is to introduce the reciprocal function $\lambda : [0,\theta(\varepsilon)] \to [0,\varepsilon]$ defined by $\theta(\lambda(t)) = t$ (this is indeed possible by the properties shown above). It is found to satisfy the Cauchy problem

$$\lambda'(t) = k\sin^2 \frac{t}{2}\,, \quad \lambda(0) = 0,$$

which gives $\lambda(t) = \frac{k}{2} \left(t - \sin t\right)$. It follows that

$$y(\lambda(t)) =k \sin^2 \frac{t}{2} \quad t \in [0,\theta(\varepsilon)].$$

This is exactly saying that $y$ coincides with $\mathcal{B}_k$ on $[0,\varepsilon]$.

$\bullet$ Step 2 Let $y$ be a solution of $(P)$ and let $\varepsilon$ be as in step 1. Then the function $\mathcal{B}_k$ solves the Cauchy problem

$$y' = F(y) = \sqrt{\frac{k-y}{y}}, \quad y(\varepsilon/2) = \mathcal{B}_k(\varepsilon/2),$$

where $F:(0,k) \to \mathbb{R}_+$ is locally Lipschitz. Since $\mathcal{B}_k$ is well-defined on $[0,s_0]$ and solves the above on the whole interval $(0,s_0)$, and since $y$ is a local solution of the same problem, $y$ and $\mathcal{B}_k$ coincide on $[0,\min(a,s_0)]$, using the fact that they are both restrictions of a unique maximal solution. If $a< s_0$, we immediately deduce statement B. If not, then $y|_{[0,s_0]} = (\mathcal{B}_k)|_{[0,s_0]}$. In particular, $y'(s_0) = 0$.

From now on, we assume that $a > s_0$

[Edit: filled in the gaps in step 3]

$\bullet$ Step 3 There are three cases : $y_a = k$, $y_a = 0$ and $y_a \in (0,k)$.

If $y_a = k$, then $y'(a) = 0$ and we conclude step $3$ with $s_\infty = a$.

If $y_a = 0$, then we use the change of variables $z(x) = y(a - x)$. Then $z$ also solves $(P)$, and by steps $1$ and $2$, it agrees with $\mathcal{B}_k$ on $[0,s_0]$. We deduce that $y$ agrees with $x \mapsto \mathcal{B}_k(a-x)$ on $[a-s_0,a]$ and $y'(a-s_0) = 0$. We cannot have $a - s_0 < s_0$ because this would mean there exists $\xi \in (a-s_0,s_0)$ such that $\mathcal{B}_k$ and $x \mapsto \mathcal{B}_k(a-x)$ coincide near $\xi$, but the first one is strictly increasing and the second, strictly decreasing. Therefore, $a - s_0 > s_0$, showing step 3 in this case with $s_\infty = a - s_0$.

Finally, suppose $y_a > 0$. Then $y'(a)$ is given by

$$y'(a) = \pm \sqrt{\frac{k-y_a}{y_a}} \neq 0$$

Let us show that it is the negative sign. For this, assume by contradiction that $y'(a) > 0$. Then let

$$U = \{x \in (0,a] : y'(t) > 0 \text{ for all } t\in [x,a]\}.$$

Then $a \in U$ and $\inf U \geq s_0$. Let $\xi = \inf U \in (0,a)$. Since $y'$ is increasing on $[\xi,a]$, we have $y(\xi) \leq y_a < k$. On the other hand by continuity, $y'(\xi) = 0$ so $y(\xi) = k$ : contradiction. So $y'(a) < 0$. By continuity, $y$ satisfies

$$y'(x) = -\sqrt{\frac{k - y}{y}}, \quad y(a) = y_a$$

in an interval $(a-\varepsilon,a]$, where $\varepsilon$ can be chosen such that $y$ stays away from $0$ and $k$ in this interval. We can thus apply the Cauchy-Lipschitz theorem and deduce that $y$ coincides with the maximal solution to this problem, which we can exhibit. Namely, if $s^*$ is the unique solution in $(0,s_0)$ of $\mathcal{B}_k(s^*) = y_a$, then

$$y(x) = \mathcal{B}_k(s^* + a - x) $$

for all $x \in [a - (s_0 - s^*),a]$. This solution was obtained intuitively by reversing the brachistrochrone and shifting it the proper amount to satisfy the boundary condition. The fact that it is indeed a solution can be verified directly from the definition of $s^*$ and the fact that $(1 + \mathcal{B}_k'^2) \mathcal{B}_k = k$. Letting $s_\infty := a - (s_0 - s^*)$, we deduce that $y'(s_\infty) = -\mathcal{B}_k'(s_0) = 0$. Furthermore, using again the sign of the derivative, we must have $a - (s_0 - s^*) > s_0$. This gives step 3 in this case.

$\bullet$ Step 4. For completeness, the lemma mentioned is the following :

Lemma Suppose that $0 < s_0< s_\infty \leq a$ are such that $y'(s_0) = y'(s_\infty) = 0$. Then $y$ is constant equal to $k$ on $[s_0,s_\infty]$.

Since $y(x) \leq k$ for all $k$ and $y'(s_0) = 0 \implies y(s_0) = k$, we have $\max_{x \in [s_0,s_\infty]} y(x) = k$. On the other hand, suppose that $m = \min_{x \in [s_0,s_\infty]} y(x) < k$. Then there is $\xi \in (s_0,s_\infty)$ such that $y(\xi) = m$, and $y'(\xi) = 0$ because $\xi$ is a global minimum on $[s_0,s_\infty]$ and $y$ is $C^1$ near $\xi$. Thus $y(\xi) = k$, contradiction.