Can we take many $1D$ shapes with the shape of the letter v, make them stand one next to the other, and make a straight line out of it? It seems there is a kind of "height" (which the straight line lacks of) but it also seems that this height can become arbitrarily small if we multiply the number of v's (towards infinity).

This question showed up to me while watching a visual proof of Stokes' theorem. After seeing that, locally, $$ \iint_S \text{curl}\; {\bf G} \cdot d{\bf S} = \oint_C {\bf G} \cdot d{\bf r} $$

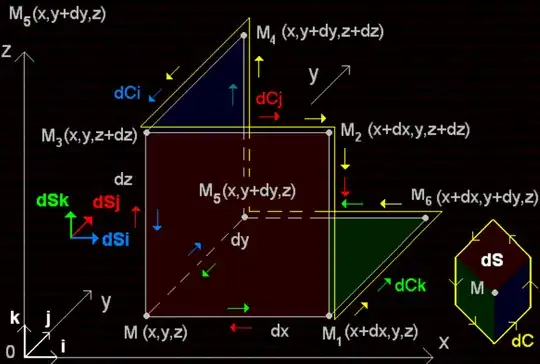

where $S$ and $C$ are taken to be infinitesimal surface and contour with a somewhat crazy shape ; they generalize the relation to a case where $S$ and $C$ are non infinitesimal surface and coutour (i.e. a random surface and a random contour) by saying we can divide a macroscopic surface into many infinitesimal surfaces (and the same applies to the corresponding contours).

My question then is, can we for example divide a disk into these crazy surfaces? Can we approximate the circle around the disk by the sum of paths such as the yellow path below?

By crazy surfaces and coutours I mean they took for the surfaces three faces (orthogonal each with another) of a cube (the red, green and blue in the image below), and for the contour, they took the yellow path, as you can see in the image below:

PS: I have already understood that when we divide a contour into smaller contours, the circulation in the interior segments cancels out. The same for surfaces.

EDIT -

I am actually trying to check the math validity of this visual proof. After reading the Wiki article on Smooth Infinitesimal Analysis, they say "lines are made out of infinitesimally small segments" (in this theory). These segments can be thought of as being long enough to have a definite direction, but not long enough to be curved.

Should I draw the conclusion that even using Smooth Infinitesimal Analysis, a straight line can't be approximated by infinitesimally small v-s? Hence, that the visual proof of Stokes theorem is wrong?

Many thanks.