This question pertains to Example 3.5 of Aluffi's "Algebra: Chapter 0", and is similar to the question asked here: Example 3.5 in Allufi: Chapter 0 (Slice categories). Let $\mathsf{C}$ be some category and $A \in \operatorname{Obj}(\mathsf{C})$. Aluffi defines a new category $\mathsf{C}_A$ where the objects are "all morphisms from any object of $\mathsf C$ to $A$, so (as I understand it), the set

$$

\operatorname{Obj}(\mathsf{C}_A) = \left\{ (Z, f) : Z \in \operatorname{Obj}(\mathsf{C}), f \in \operatorname{Hom}_{\mathsf{C}_A} (Z,A) \right\}.

$$

(Edited from $\bigcup_{Z \in \operatorname{Obj}(\mathsf{C})} \mathrm{Hom}_{\mathsf{C}}(Z, A)$ thanks to a comment).

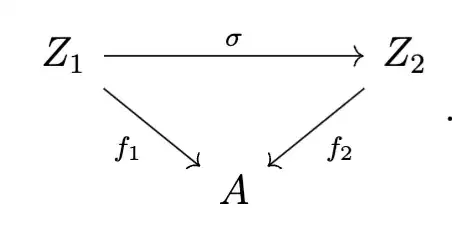

Aluffi then defines morphisms between $f_1, f_2 \in \operatorname{Obj}(\mathsf{C}_A)$ with $f_1 : Z_1 \to A$ and $f_2 : Z_2 \to A$ with $Z_1, Z_2\in \operatorname{Obj}(\mathsf C)$ as the following commutative diagram:

He states that this corresponds precisely to those $\sigma \in \mathrm{Hom}(Z_1, Z_2)$ such that $f_1 = f_2 \circ \sigma$, i.e., such that the diagram commutes.

Now, I am not entirely clear on what the set $\mathrm{Hom}_{\mathsf{C}_A}(f_1, f_2)$ is exactly. Is it the diagram, so a set of objects with a set of morphisms, as Aluffi “defines” it? Or is it those $\sigma$ themselves, so

$$ \operatorname{Hom}_{\mathsf{C}_A}(f_1,f_2) = \left\{ \sigma \in \mathrm{Hom}_{\mathsf{C}}(Z_1, Z_2) : f_1 = f_2 \circ \sigma \right\}? $$ If this right, is it possible to have the actual diagram (whatever that really is, the definition in the book is somewhat unclear to me) as morphisms of some category, as Aluffi's language suggests?

Apologies if this is a somewhat silly question, but I would like to make sure that I don't have a wrong understanding of this (apparently important) example from the beginning!