Short answer (glib)

The expression isn't well-defined, so it's not meaningful to assign a value to infinite continued fraction.

Short answer (sincere)

It's reasonable to assign the value of $1$ to the infinite continued fraction, although there's a caveat, explained below.

Longer answer

We can construct a sequence of rational numbers by beginning with some initial seed $x_0$ and iterating the function

$$

f(x) = \frac{2}{3-x}.

$$

In other words, we let $x_1 = f(x_0)$, then $x_2 = f(x_1)$, then $x_3 = f(x_2)$, and in general, for any natural number $n$,

$$

x_{n+1} = f(x_n).

$$

Notice that we can chain these together, so that, e.g.,

$$

x_3 = f(x_2) = f\bigl(f(x_1)\bigr) = f\Bigl(f\bigl(f(x_0)\bigr)\!\Bigr),

$$

which we can also write with superscript notation: $x_3 = f^3(x_0)$, and in general $x_n = f^n(x_0)$. Expressing this in a more intuitive manner, the term $x_n$ is the result of $n$ applications of the function $f$:

$$

x_0 \overset{f}{\mapsto} x_1 \overset{f}{\mapsto} x_2 \overset{f}{\mapsto} \cdots \overset{f}{\mapsto} x_n

$$

As an example, let's take $x_0 = \color{blue}{0}$. Then,

$$

x_1 = f(\color{blue}{0}) = \frac{2}{3 - \color{blue}{0}} = \color{green}{\tfrac{2}{3}},

$$

and

$$

x_2 = f\bigl(\color{green}{\tfrac{2}{3}}\bigr) = \frac{2}{3 - \color{green}{\tfrac{2}{3}}} = \color{red}{\tfrac{6}{7}}.

$$

This generates the sequence

$$

0, \frac{2}{3}, \frac{6}{7}, \frac{14}{15}, \frac{30}{31}, \frac{62}{63}, \dots

$$

You might even recognize a pattern there since both the numerator and denominator are very close to powers of $2$:

$$ x_n = \frac{2^{n+1}-2}{2^{n+1}-1} = 1 - \frac{1}{2^{n+1}-1}$$

It's pretty clear, at least with the seed $x_0 = 0$ that

$$

\lim_{n \to \infty} x_n = 1.

$$

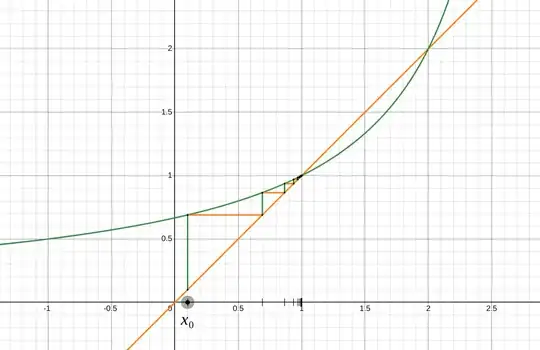

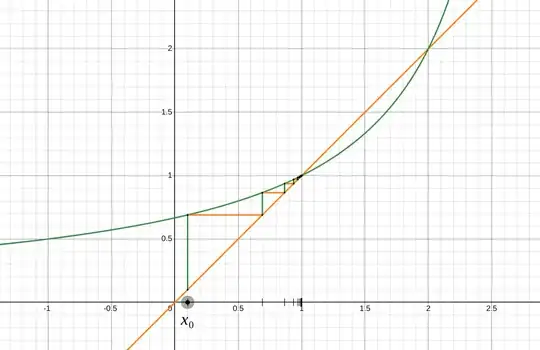

But what about other seeds? It turns out that for any real number seed with some important exceptions$^\dagger$ the sequence $\{x_0, x_1, x_2, \dots\}$ also converges to $1$. In this interactive graphic, you can drag the seed $x_0$ to various values (or type it in on the left), and watch it generate the sequence of values. Notice how they always find their way to $1$ for this particular function $f$.

${}^\dagger$Since $f(2) = 2$, the iterates form the constant sequence $\{2, 2, 2, \dots\}$, clearly with limit $2$. This is special since although its a fixed point, it's unstable, which means that any nearby number, no matter how close, moves away from $2$.

Edited to include the following, thanks to the comment of Federico Poloni: The other exceptions fit into an infinite family. Evidently, $x_0 = 3$ doesn't work because the function $f$ is undefined at $3$, so the sequence of iterates doesn't even get started. But, $x_0 = \tfrac73$ is no good either since in that case $x_1 = f\bigl(\tfrac73\bigr) = 3$ is as far as we can get. In fact, the sequence of negative iterates of $x_0 = 3$ are all problematic:

$$

\bigl\{ \dots, f^{-3}(3), f^{-2}(3), f^{-1}(3), f^{-1}(3), 3 \bigr\}

= \bigl\{ \dots, \tfrac{31}{15}, \tfrac{15}{7}, \tfrac{7}{3}, 3 \bigr\}.

$$

Although there are infinitely many of these bad seeds, they are like dust, discrete points among a continuum of other potential seeds, so in a meaningful sense, they're negligible. For instance, there's zero probability that you would pick any one of them if you picked a random real number seed (uniformly) on some interval of real numbers. Perhaps you can come up with a formula for these numbers, beginning with working out a formula for the inverse $f^{-1}(x)$?

\cfracinstead of\fracfor continued fractions. It makes them bigger, which improves readability, but they take more space. – CiaPan Dec 05 '24 at 06:53