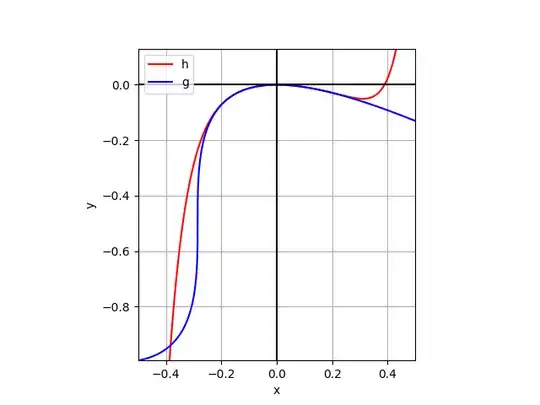

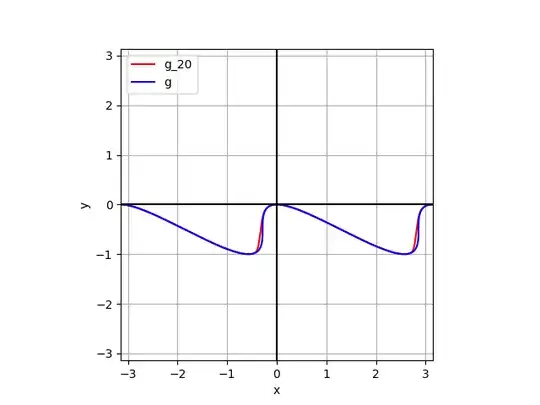

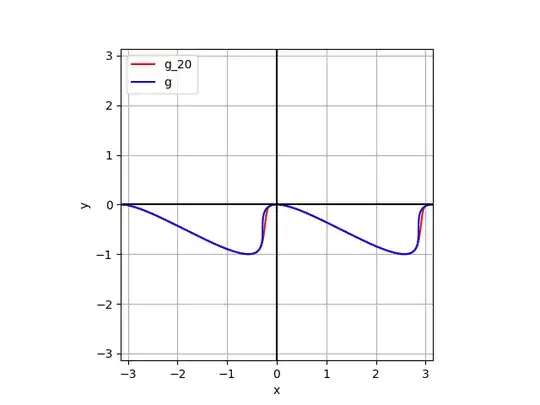

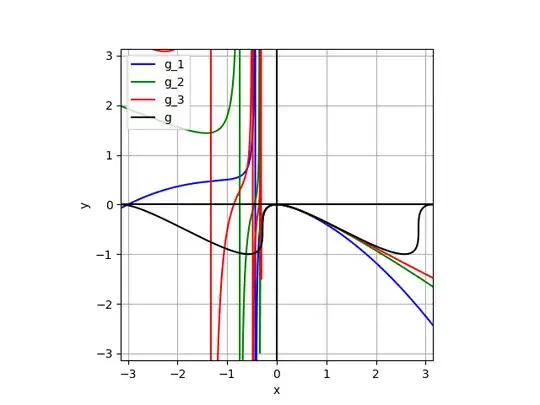

We can also try to use Padé approximants to $g$.

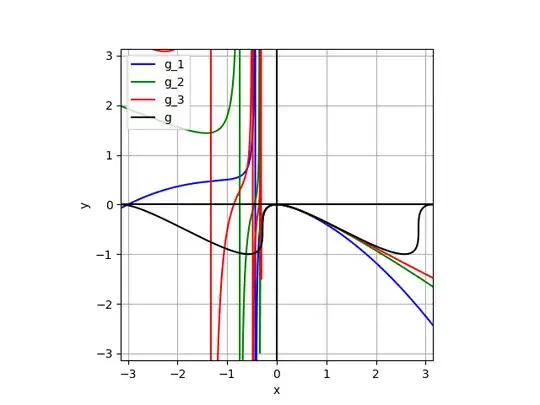

In this first example, we compute Padé approximants $\frac{p_k}{q_k}$ with $\operatorname{deg}(p_k) = \operatorname{deg}(q_k) = k$ such that with $g_k(x) = x^2 \frac{p_k(x)}{q_k(x)}$ we have $g \approx g_k$ ($1 \leq k \leq 3$).

import flint

import numpy as np

import scipy as sp

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

x_series = flint.fmpq_series([0,1])

f_series = x_series + x_series.sin()2

f_inv_series = f_series.reversion()

g_series = f_inv_series - x_series

h_series_abstract = g_series / x_series2

h_series = [int(coeff_abstract.p) / int(coeff_abstract.q) for coeff_abstract in h_series_abstract.coeffs()]

xs = np.linspace(-np.pi, np.pi, 10**3 + 1)

yss = []

for n in range(1, 3 + 1):

h_pade_p, h_pade_q = sp.interpolate.pade(h_series, n, n)

print([h_pade_p, h_pade_q])

def h_pade(x):

return x*2 h_pade_p(x) / h_pade_q(x)

ys = np.vectorize(h_pade)(xs)

yss.append(ys)

plt.plot(xs, yss[0], color="blue", label="g_1")

plt.plot(xs, yss[1], color="green", label="g_2")

plt.plot(xs, yss[2], color="red", label="g_3")

a = np.linspace(-np.pi, np.pi, 103 + 1)

b = a + np.sin(a) 2

c = b

d = a - b

plt.plot(c, d, color="black", label="g")

plt.grid()

plt.axhline(color="black")

plt.axvline(color="black")

ax = plt.gca()

ax.set_xlim([-np.pi, np.pi])

ax.set_ylim([-np.pi, np.pi])

ax.set_aspect('equal')

plt.legend(loc="upper left")

plt.xlabel("x")

plt.ylabel("y")

plt.savefig("out.png")

plt.show()

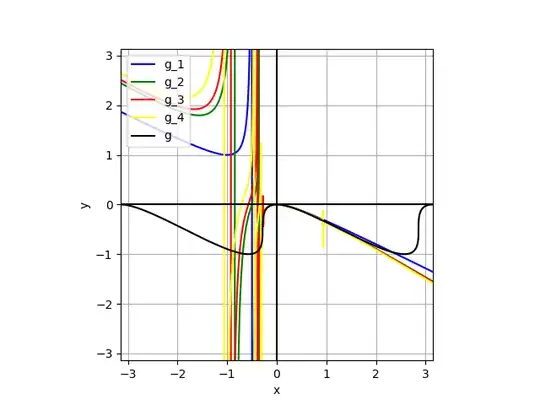

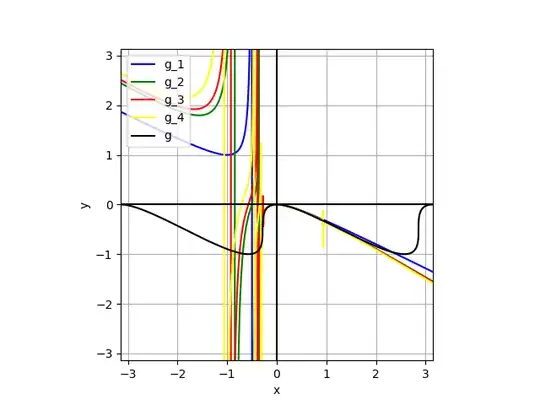

In this second example, we compute Padé approximants $\frac{p_k}{q_k}$ with $\operatorname{deg}(p_k) = \operatorname{deg}(q_k) = k$ such that with $g_k(x) = x \left( \frac{p_k(x)}{q_k(x)} - 1 \right)$ we have $g \approx g_k$ ($1 \leq k \leq 4$).

import flint

import numpy as np

import scipy as sp

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

x_series = flint.fmpq_series([0,1])

f_series = x_series + x_series.sin()**2

f_inv_series = f_series.reversion()

h_series_abstract = f_inv_series / x_series

h_series = [int(coeff_abstract.p) / int(coeff_abstract.q) for coeff_abstract in h_series_abstract.coeffs()]

xs = np.linspace(-np.pi, np.pi, 10**3 + 1)

yss = []

for n in range(1, 4 + 1):

h_pade_p, h_pade_q = sp.interpolate.pade(h_series, n, n)

print([h_pade_p, h_pade_q])

def h_pade(x):

return x * (h_pade_p(x) / h_pade_q(x) - 1)

ys = np.vectorize(h_pade)(xs)

yss.append(ys)

plt.plot(xs, yss[0], color="blue", label="g_1")

plt.plot(xs, yss[1], color="green", label="g_2")

plt.plot(xs, yss[2], color="red", label="g_3")

plt.plot(xs, yss[3], color="yellow", label="g_4")

a = np.linspace(-np.pi, np.pi, 103 + 1)

b = a + np.sin(a) 2

c = b

d = a - b

plt.plot(c, d, color="black", label="g")

plt.grid()

plt.axhline(color="black")

plt.axvline(color="black")

ax = plt.gca()

ax.set_xlim([-np.pi, np.pi])

ax.set_ylim([-np.pi, np.pi])

ax.set_aspect('equal')

plt.legend(loc="upper left")

plt.xlabel("x")

plt.ylabel("y")

plt.savefig("out.png")

plt.show()

We see that in both cases, the approximations go wild beyond the first vertical slope.