Consider the following claim:

Claim: Suppose $B^d$ (the unit ball in $\mathbb{R}^d$) is contained in the convex hull of $A$. Then, for every $\epsilon> 0$ there is a finite subset $A_f \subseteq A$ such that $(1-\epsilon)B^d \subseteq \mathrm{conv}(A_f)$.

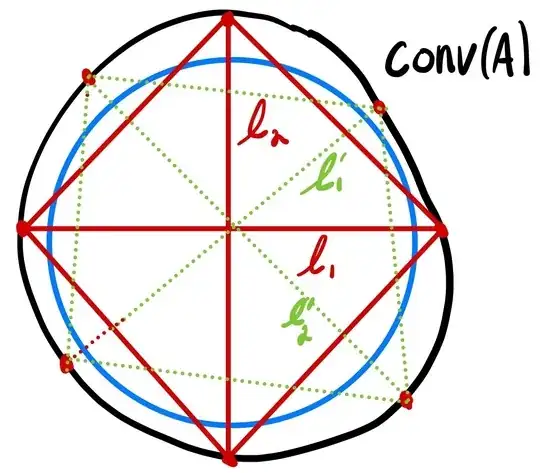

My idea of how to prove this is as follows. Consider $d$ pairwise orthogonal lines through the origin $\ell_1,\dots, \ell_d$. These lines each intersect the boundary of $\mathrm{conv}(A)$ at the points $x_1,y_1$ for $\ell_1$, $x_2,y_2$ for $\ell_2$ etc. Taking the convex hull of $\{x_1,y_1,\dots, x_d,y_d\}$ gives a cross polytope that covers a large (?) portion of the the ball.

By Caratheodory, each $x_i$ and $y_i$ is contained in the convex hull of at most $d+1$ points (actually $d$ points since they're on the boundary) from $A$. My thought is to then rotate these lines finitely many times. After each rotation, add the points from $A$ that convex the intersection points of these lines with the boundary of $A$ to my finite set.

Intuitively it should be that $(1-\epsilon)B^d$ is contained in the convex hull of the set of points obtained after "enough" iterations of this process. However, I have been struggling to write a precise, analytic proof of this.

Any thoughts on how to continue would be greatly appreciated.

UPDATE: By the way it is not too hard to prove this in the plane. Roughly one takes a regular $2n$-gon inscribed in the unit circle. Then the inradius of the $2n$-gon is $\cos\left(\frac{\pi}{2n}\right)$ which tends to $1$ as $n\to \infty$. Thus we can just take the vertices to be those of the $2N$-gon and each of those vertices are contained in the convex hull of at most $d+1$ (so $3$ since we're in the plane) so we can take $6N$ vertices for large enough $N$.