Update: Full solution to this problem

Note: I know squeeze theorem, polar coordinate,... they can solve the example but they are not generalizable. I put the example in the title so people can relate and understand what is the main topic but it is not the main focus of what I'm asking.

I had trouble understanding the nature of multivariable limits so I tried to find a method to solve as many problems as I could, or even better, I can have a visual of how it works by implementing it on calculators.

I will take the following limit as an example

$\lim_{(x,y)\to (0,0)} \frac{x^{3}y}{x^{4}+y^2} $.

Firstly, I will narrow the limit $(x,y)\to (0,0)$ down to $(x,y)\to (0^{+},0^{+})$, the complement limits can be achieved either by fixing one variable at $0$ or change of variables get the principle limit $(x,y)\to (0^{+},0^{+})$. Now, I'd like to introduce a "free parameter" $\alpha:=\frac{\ln(1/y)}{\ln(1/x)}>0$ for all $(x,y)\to (0^{+},0^{+})$, equivalently $y=x^\alpha$. We see that $\alpha$ only requires positivity and it is run freely on $(0,+\infty) $ during the limit process, now we substitute $y=x^\alpha$ into the narrowed limit:

$$\lim_{(x,y)\to (0^{+},0^{+})} \frac{x^{3}y}{x^{4}+y^2} = \lim_{x\to 0^{+}} \frac{x^{3+\alpha}}{x^4+x^{2\alpha}}= \lim_{x\to 0^{+}} \left(x^{1-\alpha}+x^{-3+\alpha}\right)^{-1}$$

For all $\alpha \in (0,+\infty)$, atleast $1-\alpha$ or $-3+\alpha$ is negative so no matter how we let $\alpha$ run, $x^{1-\alpha}+x^{-3+\alpha}$ will always approach infinity when $x\to 0^{+}$, thus we conclude:

$$\lim_{(x,y)\to (0^{+},0^{+})} \frac{x^{3}y}{x^{4}+y^2}=0$$

The first example is done here.

I will also provide how I generalize the method, for example:

$$\lim_{(x,y,z)\to (0^{+},0^{+},0^{+})}\frac{xy+z}{x^2+y^2+z^2}\overset{(y=x^{\alpha},z=x^{\beta})}{=} \lim_{x\to 0^{+}} \left((x^{1-\alpha}+x^{\alpha-1}+x^{2\beta-\alpha-1})^{-1}+(x^{2-\beta}+x^{2\alpha-\beta}+x^{\beta})^{-1}\right)$$

There are 2 parameters, things are not obvious for human but I think Linear Programming could handle them.

Question:

How good/correct this method is? In what cases it can go wrong?

I assume that the indeterminate limit in question has this form:

$$\lim_{(x_1,...,x_n)\to(0^{+},...,0^{+})} \frac{\sum_{i}c_{1i}x_{1}^{a_{i1}}...x_{n}^{a_{in}}}{\sum_{j}c_{2j}x_{1}^{b_{j1}}...x_{n}^{b_{jn}}}$$

where $c_{1i},c_{2j}>0$ and $a_{ik},b_{jk}\in \mathbb{R}$

Extension

I took one step furthur into the investigation and suprisingly, this is what I found: (below is an example but I think it is enough for you to see what's going on):

$$L=\lim_{(x,y)\to (0^{+},0^{+})}\frac{x^{a}y^{b}}{x^{7}+x^{4}y+xy^{3}+y^{5}}$$

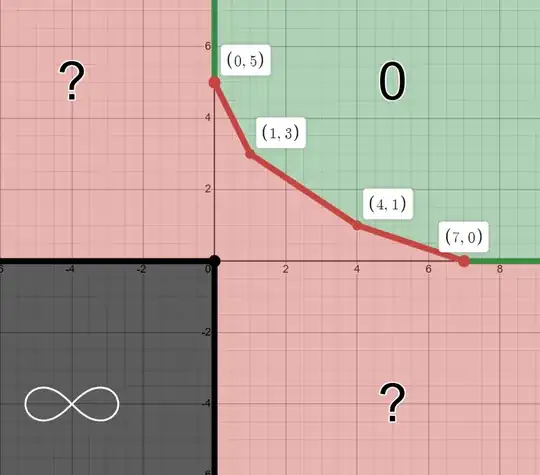

The image below is graph of limit with respect to $(a,b)$ in $\mathbb{R}^{2}$

Note that colors of edges and points are counted

(green=limit is $0$; red=essentially undecidable; black=limit is $+\infty$)

The logic seems to apply consistently with computation result, my method agrees too.

So "Polytopes solve limits"?

I will leave this as an unproven conjecture (the generalized in n dimensions) for anyone who is interested. Any ideas are appreciated.