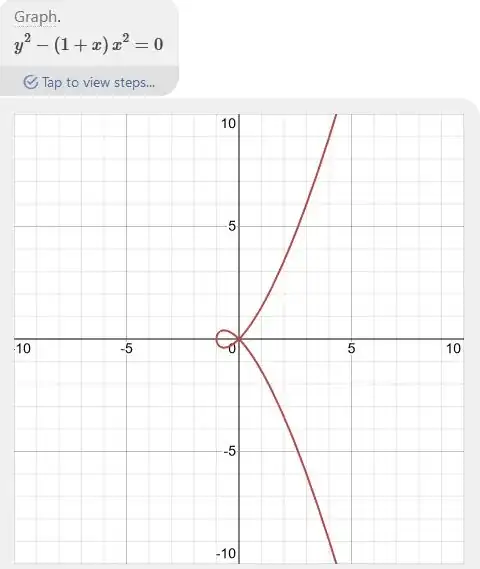

Let be $\,\,f:\mathbb{R} \setminus \{1\} \to \{(x,y) \in \mathbb{R}^2 : y^2=x^2(1+x)\} \,\,$ with $\,\,\,f(t)=(t^2-1,t(t^2-1))$, prove that for all $x \in \mathbb{R}\setminus \{1\}$ exists a neighborhood $U$ of $x$ such that $f:U \to f(U)$ is a homeomorphism.

Now $f$ is continuous and bijective and I want to show that if $t \in \mathbb{R} \setminus \{1\}$ exists a $\delta>0$, if necessary we can take $\delta$ so that $t-\delta>1\,\,\,$ or\and $\,\,t+\delta<1\,\,\,$, such that $\,\,\,f: (t- \delta, t+ \delta) \to f((t- \delta, t+ \delta))\,\,\,$ is a open map, that is for all $u \in (t- \delta, t+ \delta)\,\,$ exists a $\,\,\,\epsilon >0\,\,\,\,$ such that $\,\,\,\,B_{\mathbb{R}^2}(f(u),\epsilon)\,\,\cap\,\, \{y^2=x^2(1+x)\} \subseteq f((t- \delta, t+ \delta))$.

I think that $\epsilon < \mathrm{min} \, \{|t-u|,|t+u|\}$ could work, any hint to show it properly? If I am not wrong.