Suppose the sphere has radius $1$ and is centered at the origin. Then we can partition the x-integral $[-1,1]$, (see $-1=x_0<x_1<\cdots <x_n=1$) and each piece has the area "seems can be approxiated" by $2\pi \sqrt{1-x^2} \Delta x_i$, where $\Delta x_i =x_{i}-x_{i-1}$, and $x\in [x_{i-1},x_i]$. The idea is that the area in this piece is roughly a rectangle with length $2\pi \sqrt{1-x^2}$ and width $\Delta x_i$. Saving the notation, one has $2\pi \sqrt{1-x^2} dx$. Then we integrate it to obtain the area of the sphere is $$ \int_{-1}^{1} 2\pi \sqrt{1-x^2} dx = \pi^2. $$ This is not coincide with the well-known formula which is $4\pi$. What goes wrong? I can not explain well to convince myself. Thank you very much.

Asked

Active

Viewed 74 times

0

-

1It is a surface-area version of this "$\pi=4$ fallacy". This tells that when approximating the measure of a geometric figure, especially a low-dimensional one, must be taken great care. This is because the "approximation" in one sense (for instance, in Hausdorff distance) does not guarantee the approximation of the corresponding measure. Or saying differently, such measures need not necessarily be continuous in the given topology of geometric figures. – Sangchul Lee Nov 01 '24 at 02:31

-

1Replace $dx$ with $ds=\sqrt{1+(\frac{dy}{dx})^2}dx$ where $ds$ is a small piece of length of the circle. – John Douma Nov 01 '24 at 02:42

1 Answers

3

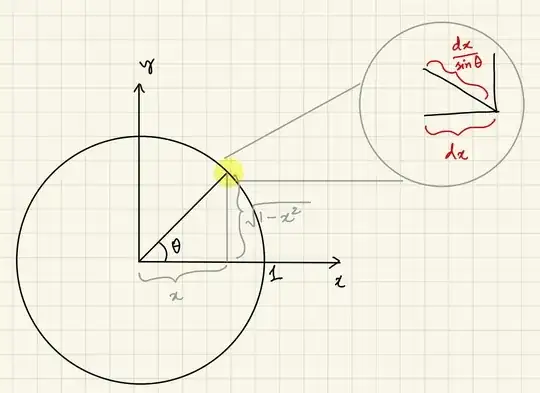

You missed an additional factor of $1/\sqrt{1-x^2}$ inside the integral. While you got the length of each rectangular piece right, you didn’t get the width right. It’s not just $dx$. It should be $dx/\sin \theta$, where $\theta$ is the angle made by the radial vector at that point with the $x$-axis in your notation. The sine of this angle is simply $\sqrt{1-x^2}$.

Here’s an illustration that might explain it better:

Pranay

- 5,390