I'm trying to understand how the interpretations of $k$-dimensional holes comes from the quotient group definition of Homology Groups.

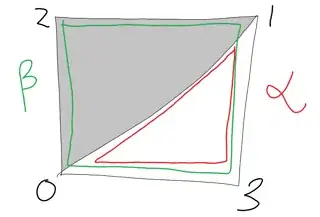

Taking $\partial_k$ as the $k$-dimensional boundary operator on a simplicial complex $X$. The $k$-th homology group of $X$ is: \begin{equation} $$ \tag{1} H_k(X) = \frac{\ker(\partial_k)}{\text{Im}(\partial_{k+1})}. $$ This is commonly said to be interpreted as the $k$-dimensional holes present in the simplicial complex. In this paper, it is stated that $H_k(X)$ is: $$ \tag{2} H_k(X) = \ker(\partial_k)\cap\big(\text{Im}(\partial_{k+1})\big)^C, $$ basically saying that the $k$-th homology group consists of the cycles that are not boundaries of a $(k+1)$-dimensional simplex.

This second interpretation of a $k$-dimensional hole makes sense to me but I'm having difficulty understanding how to go from (1) to (2) as my understanding is also that the elements in (1) are basically sets of cycles while the elements in (2) are simply cycles. Any help disambiguating this is appreciated.