A more traditional and elaborate geometrical proof.

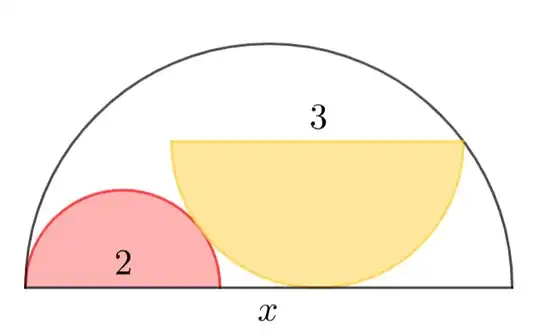

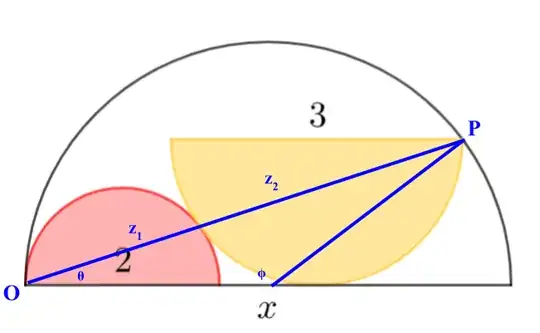

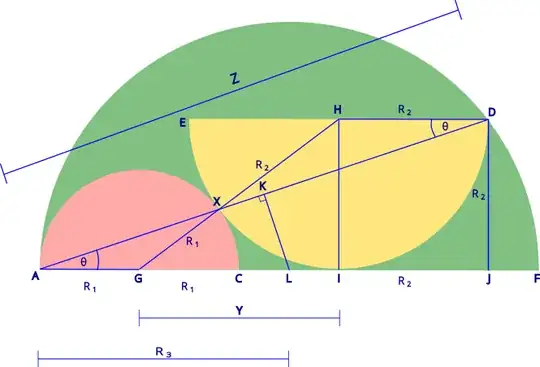

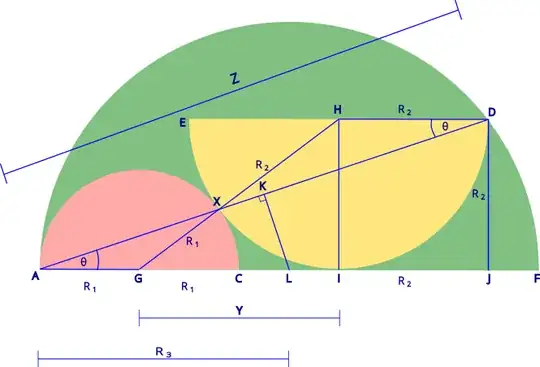

Let's look at the general situation for any pair of semi-circles $R_1$ and $R_2$ such that $R_1 < R_2$.

Consider $\triangle GHI$ and let $Y = |GI|$

By Pythagoras:

$$ Y = \sqrt{(R_1 + R_2)^2 - R_2^2} = \sqrt{R_1^2 + 2R_1R_2} \tag{ . . . 1}$$

Now observe that $|AD|$ is a chord of the enclosing semicircle of radius $R_3$.

As such, a perpendicular line from its mid-point $K$ onto the enclosing semi-circle's diameter $|AF|$ will intersect the latter at its center point $L$ so that $|AL| = R_3$.

Thus if $\;\; Z = |AD| \;\; $ and $\;\; \angle JAD = \theta \;\;$ we have

$$ Z = \sqrt {(R_1 + R_2 + Y)^2 + R_2^2)} \tag{ . . . 2} \\ \\$$

$$ \begin{align} R_3 &= \dfrac{\dfrac{Z}{2}}{\cos{\theta}} \\ \\ \text{Since} \;\;\;\; \cos \theta &= \dfrac{R_1 + Y + R_2}{Z} \\ \\ R_3 &= \dfrac{\dfrac{Z}{2}}{\dfrac{(R_1+R_2+Y)}{Z}} \\ \\ &= \dfrac{\dfrac{Z^2}{2}}{R_1+R_2+Y} \end{align} $$

Applying (2): $$ \begin{align} R_3 &= \dfrac{1}{2}\left[\dfrac{(R_1+R_2+Y)^2 + R_2^2}{R_1+R_2+Y}\right] \\ \\ &= \dfrac{1}{2}\left[R_1+R_2+Y + \dfrac{R_2^2}{R_1+R_2+Y}\right] \tag{ . . . 3} \end{align}$$

Noting that $$\begin{align} \dfrac{R_2^2}{R_1+R_2+Y} \; &= \; R_2^2 \; \left[\dfrac{1}{R_1+R_2+Y} \; . \; \dfrac{R_1+R_2-Y}{R_1+R_2-Y} \right] \\ \\ &= \; R_2^2 \; \left[\dfrac{R_1+R_2-Y}{(R_1+R_2)^2 - Y^2} \right] \end{align}$$

$$ $$

And since from (1): $ \;\; Y^2 = R_1^2 + 2R_1R_2 $

$$ $$

$$ \begin{align} \require{cancel} \implies \dfrac{R_2^2}{R_1+R_2+Y} \; &= \; \cancel{R_2^2} \; \left[\dfrac{R_1 + R_2 -Y}{\cancel{R_1^2} + \cancel{2R_1R_2} + \cancel{R_2^2} - \cancel{R_1^2} - \cancel{2R_1R_2}}\; \right] \\ \\ &= \; R_1+R_2-Y \tag{ . . . 4} \end{align}$$

Putting result (4) into expression (3):

$$ \require{cancel} R_3 = \dfrac{1}{2} \; \left[R_1 + R_2 + \cancel{Y} + R_1 + R_2 - \cancel{Y} \right] $$

So we finally have: $$ \boldsymbol{ {R_3 \; = \; R_1 \; + \; R_2} } \\ \\ $$

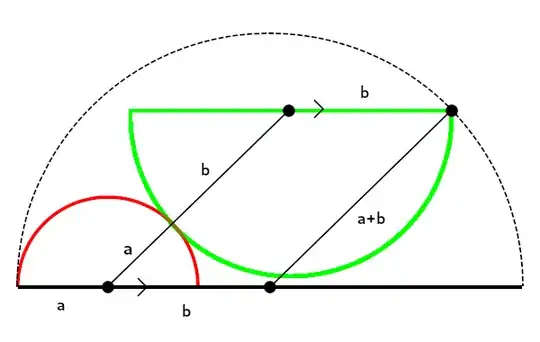

Alternative Easier Solution

Similar isosceles triangles $\triangle AGX$ and $\triangle DHX$:

$$ \begin{align} |AD| \; &= \; |AX| + |XD| \\ \\ |AD| \; &= \; 2R_1\cos{\theta} + 2R_2\cos{\theta} \\ \\ \; &= \; 2\cos{\theta}\;(R_1 + R_2) \\ \\ R_3 \; &= \; |AL| \\ \\ \; &= \; \dfrac{|AK|}{\cos{\theta}} \\ \\ |AK| \; &= \; \dfrac{|AD|}{2} \\ \\ \require{cancel} \text{Hence} \;\;\;\;\;\;\; R_3 \; &= \; \dfrac{\cancel{2\;\cos{\theta}}\;(R_1 + R_2)}{\cancel{2\;\cos{\theta}}} \\ \\ \text{Thus} \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\; \boldsymbol{ R_3}\; &= \; \boldsymbol{R_1 + R_2} \end{align} $$

$$ $$

As to the proof of the chord line $|AD|$ and the line joining the centers of the two semi-circles $|GH|$ meeting at the contact point, we can see from my diagram that this must be the case as $\triangle AGX $ and $\triangle DHX $ are similar triangles with ratio of their sides of $R_1:R_2$.

It seems to me that this ratio may only be maintained if $|GX| = R_1$ and $|HX| = R_2$ - which of course means that $|AD|$ goes through the tangent point of the semi-circles.

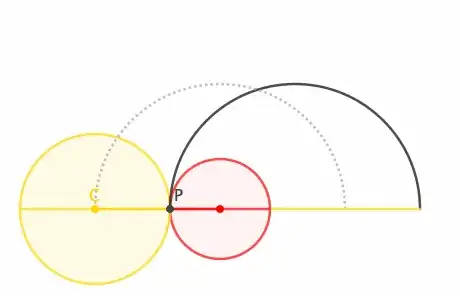

The curious thing for me is that having the larger semi-circle wide side up doesn't save space over having it wide side down. The answer from Pranay only partly satisfies me on this. It might be better to simulate a rotation of the larger semi-circle about a horizontal axis through the contact point. After $90^\circ$ of turning more horizontal space will be needed by the larger semi-circle since its wider part is now bearing upon the smaller semi-circle.

This reminds me of how both flank pieces of a shoe pattern are not too different in size despite the clear difference in the shape of the two sides of a shoe last. For centuries this fact was exploited by shoe factories: they got a sort of graphical average of the two patterns (the so-called mean forme) and exploited the stretchiness of leather to make up the differences. This process also allowed them to only need a single pressing die to click out right and left flank-pieces from a hide for each shoe-style/size combination - a significant saving in tooling costs. Nowadays laser-guided contour blades cut shoe patterns from a hide but looking at shoes the actual patterns seem to be designed the same old way !

In the case above, the two semi-circle arrangements are precisely wrapped by the same enclosing semi-circle. This makes me wonder if such an idea could be exploited in designing precision engineered things like gears or bearings - things not yet obsolete due to advances in nanomechanical and biomechanical systems.