Question:

What are some non-trivial claims that have exactly one counterexample?

Example 1:

"There is no Pythagorean triple whose numbers are consecutive terms in a row of Pascal's triangle." There is exactly one counterexample: $\left\{\binom{62}{26},\binom{62}{27},\binom{62}{28}\right\}$. proof

Example 2:

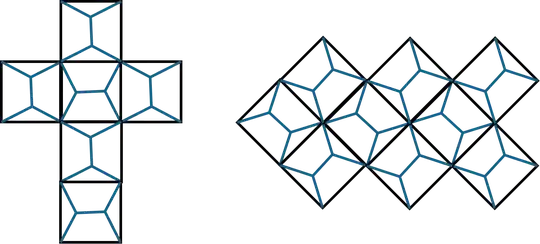

"If $n^2>1$ cannonballs are laid on the ground in a filled square formation, then they cannot all be used to make a square pyramid of cannonballs." There is exactly one counterexample: $n=70$. (from this answer)

Example 3:

"No number is equal to the sum of the subfactorials of its digits." There is exactly one counterexample: $148349$. (from this answer)

Remarks:

- It must be proven that there exists exactly one counterexample.

- Let's exclude trivially false claims, i.e. claims that are obviously false, even if one has never heard the claim before, such as "There is no even prime number" (an obvious counterexample is $2$), or "For integers $n>1$, the equation $x^n+y^n=z^n$ has no integer solutions" (an obvious counterexample is $n=2$; it is not obvious that this is the only counterexample, but the claim is still obviously false). (Note: I added the second example after a lot of answers were already given, to clarify this restriction.)

- Let's exclude ad hoc claims, i.e. claims that are purposely designed to have exactly one counterexample, such as "There is no integer $n$ such that $n=\frac{600}{\pi^2}\sum\limits_{k=1}^\infty\frac{1}{k^2}$" (the counterexample is n=100). That is, the claims should be reasonably natural claims.

This question was inspired by the question "Conjectures that have been disproved with extremely large counterexamples?".