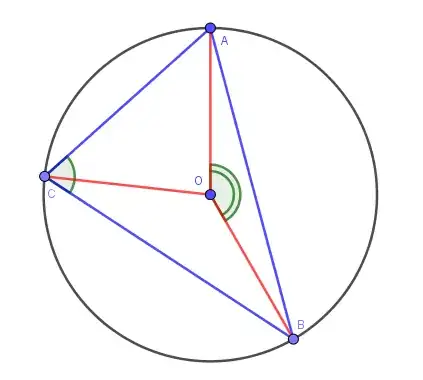

The vertices of a triangle are three independent uniformly random points on (the circumference of) a circle.

Let $X_k=\text{number of angles larger than $k\pi$}$.

Is the following conjecture true: $\mathbb{E}(X_k)=3(1-k)^2$.

If it is true, then, given its simplicity, I wonder if there is an intuitive explanation.

Evidence for my conjecture

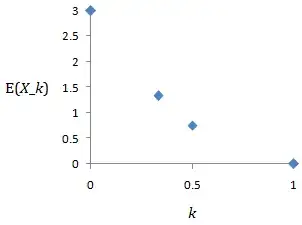

I worked out the value of $\mathbb{E}(X_k)$ for four values of $k$:

- $\mathbb{E}(X_0)=3\space$ (obvious)

- $\mathbb{E}(X_{1/3})=\frac43\space$ (explanation below)

- $\mathbb{E}(X_{1/2})=\frac34\space$ (explanation below)

- $\mathbb{E}(X_1)=0\space$ (obvious)

These points suggest the neat relationship $\mathbb{E}(X_k)=3(1-k)^2$.

Explanations

The only possible value of $X_{1/2}$ are $0$ and $1$. We know that $P(X_{1/2}=0)=\frac14$. Therefore $P(X_{1/2}=1)=\frac34$, and so $\mathbb{E}(X_{1/2})=\frac34$.

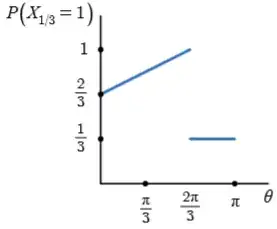

The only possible values of $X_{1/3}$ are $1$ and $2$. Let $\theta$ be the angle subtended at the circle's centre by the first two chosen points. For each value of $\theta$, we can calculate $P(X_{1/3}=1)$ by considering the total length of the arcs along which the third point must lie in order to get $X_{1/3}=1$. We get the following graph.

Averaging over $\theta$, we get $P(X_{1/3}=1)=\frac23$. Therefore $P(X_{1/3}=2)=\frac13$, and so $\mathbb{E}(X_{1/3})=\frac43$.

Using this approach with a general $k$ seems difficult. I wonder if there is an easier approach.