Let $p$ be the probability that Pascal writes a zero instead of the sum in one of the interior entries of the triangle.

Let the top row (with only one single entry) be row $0$. If Pascal writes no zeros, the sum of entries on row $n$ is $2^n$.

Suppose $0 < p < 1$ and suppose Pascal writes a triangle.

Let $X_n$ be the sum of row $n$ in the triangle

and $X_{n+1}$ be the sum of row $n+1$.

If there were no zeros in row $n+1$ then we would have $X_{n+1} = 2X_n$.

But the no-zeros version of row $n+1$ contains entries with total value $2X_n - 2$ (all entries excluding the $1$ at the start of the row and the $1$ at the end of the row), each of which can be deleted with probability $p$, so the expected value of row $n+1$ given that the sum of row $n$ is $x_n$ is

$$ \mathbb E(X_{n+1} \mid X_n = x_n) = 2x_n - (2x_n - 2)p = 2(1 - p)x_n + 2p. $$

Therefore

$$ \mathbb E(X_{n+1}) = 2(1 - p)\mathbb E(X_n) + 2p, $$

which gives us a recurrence relation with the base case $\mathbb E(X_0) = 1.$

For $p=\frac12$ the recurrence is

$$ \mathbb E(X_{n+1}) = \mathbb E(X_n) + 1. $$

The solution of the recurrence is therefore $\mathbb E(X_n) = n + 1$.

Then

$$ \mathbb E\left(\sum_{k=0}^n X_k\right) = \frac{(n + 1)(n + 2)}{2}, $$

which is also the total number of entries in rows $0$ through $n$ (inclusive),

so the expected arithmetic mean of the numbers in a triangle whose last row is row $n$ is $1$.

As $n \to \infty$, then, $1 \to 1$.

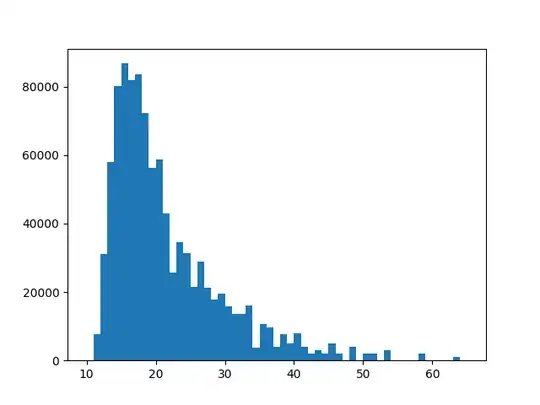

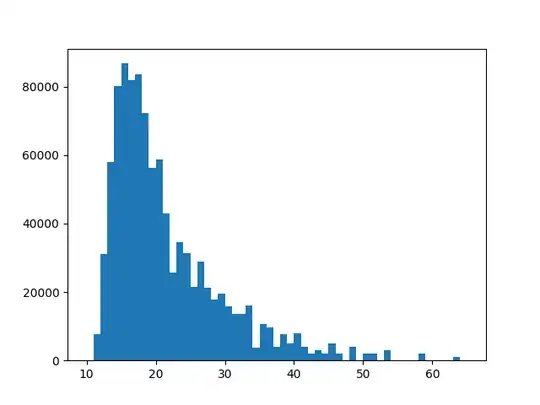

The probability distribution of the mean is highly skewed, however, which can make it difficult to estimate the mean accurately using random sampling. Here are the results of one million repetitions of a python simulation of the sum of entries in a triangle up to row $5$. The theoretical mean sum is $21$, but sums slightly less than $21$ are more likely than sums slightly greater.

I think this may help explain why you tended to find mean values less than $1$.

For $p \neq \frac12$ the solution of the recurrence is

$$ \mathbb E(X_n) = \frac{(2 - 2p)^n - 2p}{1 - 2p}. $$

Then

\begin{align}

\mathbb E\left(\sum_{k=0}^n X_k\right)

&= \sum_{k=0}^n \frac{(2 - 2p)^n - 2p}{1 - 2p} \\

&= -\frac{2(n+1)p}{1 - 2p} + \frac1{1 - 2p} \sum_{k=0}^n (2 - 2p)^n \\

&= -\frac{2(n+1)p}{1 - 2p} + \frac1{1 - 2p}\cdot\frac{(2-2p)^{n+1} - 1}{(2-2p) - 1} \\

&= \frac{(2-2p)^{n+1} - 1}{(1-2p)^2} - \frac{2(n+1)p}{1 - 2p}.

\end{align}

The mean value of entries in rows $0$ through $n$ is therefore

\begin{multline}

\frac{2}{(n+1)(n+2)}

\left(\frac{(2-2p)^{n+1} - 1}{(1-2p)^2} - \frac{2(n+1)p}{1 - 2p} \right) \\

= \frac{2(2-2p)^{n+1} - 2}{(n+1)(n+2)(1-2p)^2} - \frac{4p}{(n+2)(1 - 2p)}.

\end{multline}

If $p < \frac12$ then $2 - 2p > 1$ and the exponential function in the numerator of the first term, $(2-2p)^{n+1}$, dominates the polynomial in its denominator;

so as $n \to +\infty$,

\begin{align}

\frac{2(2-2p)^{n+1} - 2}{(n+1)(n+2)(1-2p)^2} &\to +\infty, \\

\frac{4p}{(n+2)(1 - 2p)} &\to 0,

\end{align}

so the mean value goes to $+\infty$ as $n$ goes to $+\infty$.

If $p > \frac12$ then $0 \leq 2 - 2p < 1$ and $(2-2p)^{n+1} \to 0$ as $n \to +\infty$.

Then as $n\to\infty$,

$$\frac{2(2-2p)^{n+1} - 2}{(n+1)(n+2)(1-2p)^2} \to 0, $$

so the mean value goes to $0$ as $n$ goes to $+\infty$.