I hope to better understand how to prove that a given tile can indeed tile the plane. I can often visualize the tiling and draw by hand larger and larger regions that I can tile, but I'm unsure how to argue more rigorously that a given tiling actually works. This question is based off the simplest example that I'm confident can tile the plane but that I'm not sure how to prove.

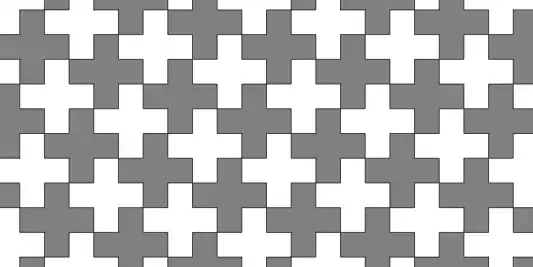

The Greek cross is a simple tile made of five squares.

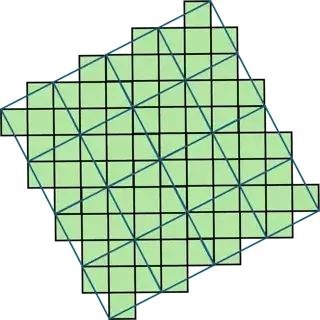

I can draw patches of the plane using these tiles.

For example, using four of these tiles:

Using nine of these tiles:

I can keep putting down Greek crosses in the spiral patterns above, and I believe that the Greek cross can tile the plane. How can I rigorously prove this?

I'm happy to view the plane as already being tiled by the faces of the square lattice, and a putative tiling as coloring such faces according to the shape of the Greek cross. I'm imagining attempting to give an explicit mapping of which face of the square lattice is part of which Greek cross, but I'm wondering if there might be a less explicit way.