I was reading a paper that claims if $K, H \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n}$, with both matrix being positive semidefinite, then $K = HW$ for some matrix $W$ iff $\operatorname{im} K \subseteq \operatorname{im} H$. I felt this can be proved by eigenvalue decomposition. However, I wonder if a more general statement can be made.

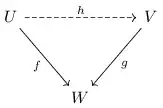

On a vector space $X$ (possibly infinite dimension) if we have two linear operators $K,H:X\to X$. Then does $\operatorname{im} K \subseteq \operatorname{im} H$ if and only if $K = H \circ W$ for some linear operator $W:X \to X$?

I cannot think of a way to prove this. In the finite dimensional case, I guess one can maybe do something such as SVD, but I felt there are simple way to prove it, or counterexamples.