It is a proof with infinitely many steps, but is generally considered unproblematic. In particular, one of the usual axioms of set theory, the Axiom of Choice, allows us to make an appropriate choice for all of the steps at once provided that at each stage an appropriate next step can be made. To be specific, I'll state an equivalent of the Axiom of Choice called Zorn's Lemma.

Zorn's Lemma. Let $\leq$ be a partial order on a set $Z$. Suppose that given any subset $A \subseteq Z$ with the property that given distinct $x , y \in A$ either $x \leq y$ or $y \leq x$ (such a sebset is called a chain in $(Z , \leq )$), there is a $z \in Z$ such that $x \leq z$ for all $x \in A$ ($x$ is an upper bound of $A$). Then there is a $z \in Z$ such that there is no $x \in Z \setminus \{ z \}$ such that $z \leq x$ ($z$ is a maximal element of $Z$).

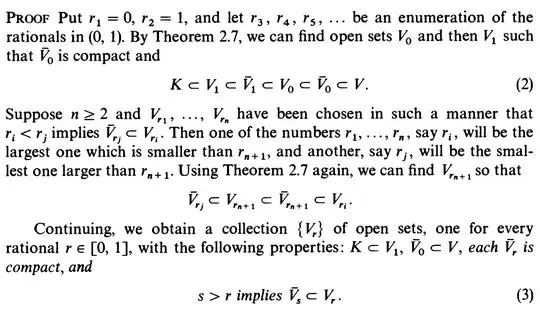

For the proof of Urysohn's Lemma, we can take $Z$ to be the set of all (finite or infinite) sequences $( V_i )_i$ which satisfy the conditions in Rudin's proof of Urysohn's Lemma up to its length. We define a partial order relation $\leq$ on $Z$ by $( V_i )_i \leq ( W_j )_j$ if $( V_i )_i$ is an initial segment of $( W_j )_i$ (i.e., $( W_j )_j$ is not shorter than $( V_i )_i$ and $V_i = W_i$ for all possible $i$). It is easy to show that every chain in $( Z , \leq )$ has an upper bound by just taking the "union" of the sequences in the chain. Then by Zorn's Lemma $( Z , \leq )$ has a maximal element $( V_i )_i$. If this maximal element happened to be finite, we could use the construction in Rudin's proof to make it longer, contradicting that it is maximal! Therefore the maximal sequence must be infinite, as required.

Note that use of a principal like the Axiom of Choice is necessary to prove Urysohn's Lemma. In

Läuchli, H., Auswahlaxiom in der Algebra, Comment. Math. Helv. 37, 1-18 (1962). ZBL0108.01002.

the author constructs a model of ZF (where the Axiom of Choice fails) in which there is an infinite normal (Hausdorff) space $X$ such that every continuous function $X \to \mathbb{R}$ is constant. This implies that Urysohn's Lemma fails in this model (since all continuous real-valued functions on $X$ are constant, you can't even separate points by continuous functions in $X$, and by Hausdorffness singleton sets are closed in $X$).

As a final aside, note that in

Good, C.; Tree, I. J., Continuing horrors of topology without choice, Topology Appl. 63, No. 1, 79-90 (1995). ZBL0822.54001.

it is proved that Usysohn's Metrization Theorem does not require the Axiom of Choice (or anything like it). Essentially, they prove that in a second-countable regular space $X$ one can use a fixed countable base $\mathcal{B}$ to define for each pair $A , B$ of disjoint closed subsets of $X$ a specific open set $U \subseteq X$ satisfying $A \subseteq U \subseteq \overline{U} \subseteq X \setminus B$. One can then prove that Urysohn's Lemma holds for this space by following, e.g., Rudin's proof of Urysohn's Lemma, but instead of choosing an intermediary set at each stage, use a previously fixed countable base to define it. Since each step was determined, one then uses the Principle of Recursive Definitions instead of the Axiom of Choice to justify that it could all be done at once.