Working through "Geometric Algebra for Computer Science: An Object Oriented Approach" on my own. The problem comes from an example on page $130$. This should be an easy calculation, why I'm all the more frustrated.

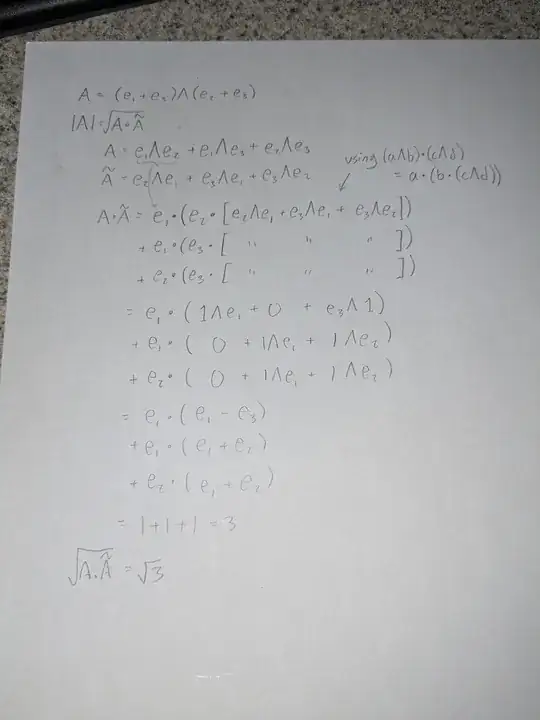

Calculating it using the general formula (see image) I get the wrong answer.

I do understand how to get $2$ by just multiplying the lengths of the vectors on either side of the wedge product, since the vectors are orthogonal, i.e., (left side) dot (right side) $= 0$. But want to understand where my mistake is in above calculation.

Thanks for your help!