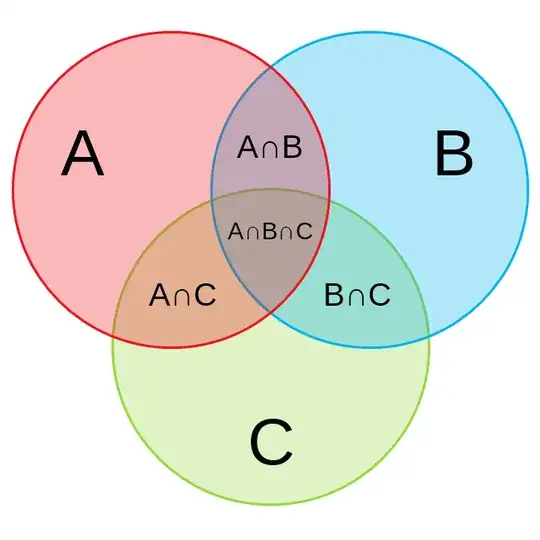

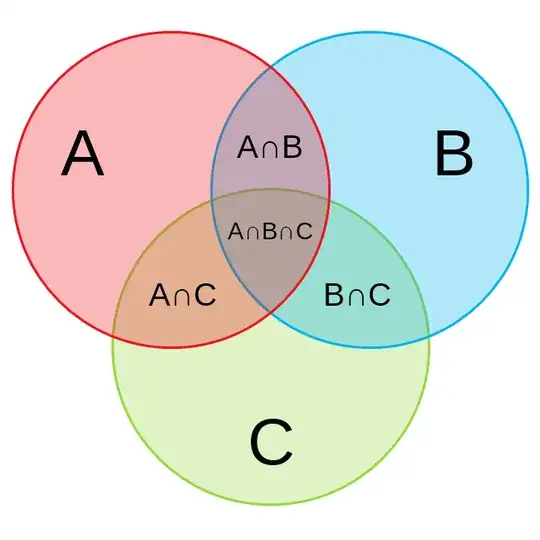

That's because $|A|+|B|+|C|$ already counts the $|A\cap B\cap C|$ $3$ times here, isn't it?

Also, this principle works for all numbers of finite sets, that is, for $n\in\mathbb{N}$ number of sets. And it has a generalized formula:

Given $X_1,\cdots, X_m $ are finite sets, $$|\bigcup_{i=1}^m X_i|=\sum_{1\le i_1\le m}|X_{i_1}|-\sum_{1\le i_1< i_2\le m}|X_{i_1}\cap X_{i_2}|+\sum_{1\le i_1<i_2<i_3\le m}|X_{i_1}\cap X_{i_2}\cap X_{i_3}|-\cdots + (-1)^{m-1} |X_1\cap \cdots \cap X_m|$$

In which for intersection of odd numbers of sets, to count the total size, we decrease the size of these sets, and add those intersections of even numbers of sets.

A proof can be done by second form of induction:

Let this statement be $P$

$P(1)$ holds as $|X_1|=1\cdot |X_1|$

Suppose $P(n)$, for natural number $n\le k$ holds, $k\ge 2$ we now prove $P(k+1)$ also holds.

Now $$\bigcup_{i=1}^{k+1} X_i=X_{k+1}\cup \bigcup_{i=1}^{k} X_i$$

We apply $|A\cup B|=|A|+|B|-|A\cap B|$ to this, which is statement $P(2)$, holds as $k\ge 2$

And we will naturally find that $P(k+1)$ also holds!