Recently I learned that in Polya's Urn starting with $m$ red balls and $n$ blue balls ... as time goes to infinity, the ratio of red to blue balls converges to its initial ratio (Polya's urn model - limit distribution). Intuitively, I interpret this as follows:

- At $t=0$, the ratio of red to blue balls is $\frac{m}{n}$

- At $t=\infty$, the ratio of red to blue balls is also $\frac{m}{n}$

This brings me to my question:

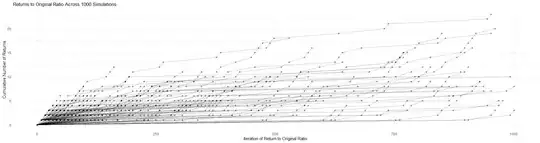

Define $t$ as the time between $(0, \infty)$, at which the ratio of red to blue balls is again $\frac{m}{n}$:

$$ \min \{ t > 0 \colon \frac{R(t)}{B(t)} = \frac{m}{n} \} $$

What is the probability distribution of $t$, $P(T=t)$ ? In other words, how long will it take for Polya's Urn to first return to the same ratio of balls as it had in the beginning?

I thought that perhaps this could be modelled as a asymmetrical Random Walk, and thus we could treat this problem as a Hitting Time Distribution question (e.g. First Hitting Time Distribution of a Random Walk with Drift follows an Inverse Gaussian Distribution), but I was not sure how to set this up.

Instead, I tried to find out the Expected Value and Variance of $t$.

1) Expected Value: Start with

$$m = \text{initial number of red balls}$$ $$n = \text{initial number of blue balls}$$

The total number of balls at the start is:

$$N = m + n$$

In Polya's Urn model, the ratio of red to blue balls at t = ∞ converges to the initial ratio:

$$\lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{R(t)}{B(t)} = \frac{m}{n}$$

where $R(t)$ and $B(t)$ are the numbers of red and blue balls at time $t$.

To find when we expect the ratio to be $m:n$ again, we need to consider the expected number of balls added before this occurs. Let's call this as x.

We can define a logical relationship as:

$$\frac{m+x\frac{m}{m+n}}{n+x\frac{n}{m+n}} = \frac{m}{n}$$

Solving this equation:

$$\frac{m(m+n)+xm}{n(m+n)+xn} = \frac{m}{n}$$

$$m(m+n)+xm = m(m+n)+xm$$

$$E(T) = x = m+n = N$$

Thus, it seems as if once you after $N$ turns have passed such that $N$ equals the original number of balls - the ratio of red to blue balls after $N$ turns will also be the same as the ratio of red to blue balls at the start.

2) Variance I am unsure how to calculate the Variance . I started doing this:

$$P(\text{red at t}) = \frac{X_t}{X_t + Y_t}$$

$$E(T^2) = \sum_{t=1}^{\infty} t^2 \cdot P(T=t)$$

But I am not sure how to continue.

Can someone please show me how to derive the variance for the time in this problem? And is it possible to get a PDF (rather PMF) for the time?

Notes:

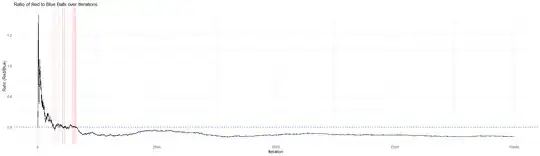

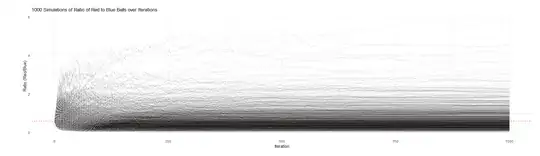

Edit: Some Visualizations of an Urn that starts with a ratio of 3:5 and how it returns to its original ratio (I can include the R code if anyone is interested):